In partnership with MiCodmc, a selection of establishments ripe for discovery during the 63rd edition of the Salone del Mobile.Milano, from 8th to 13th April

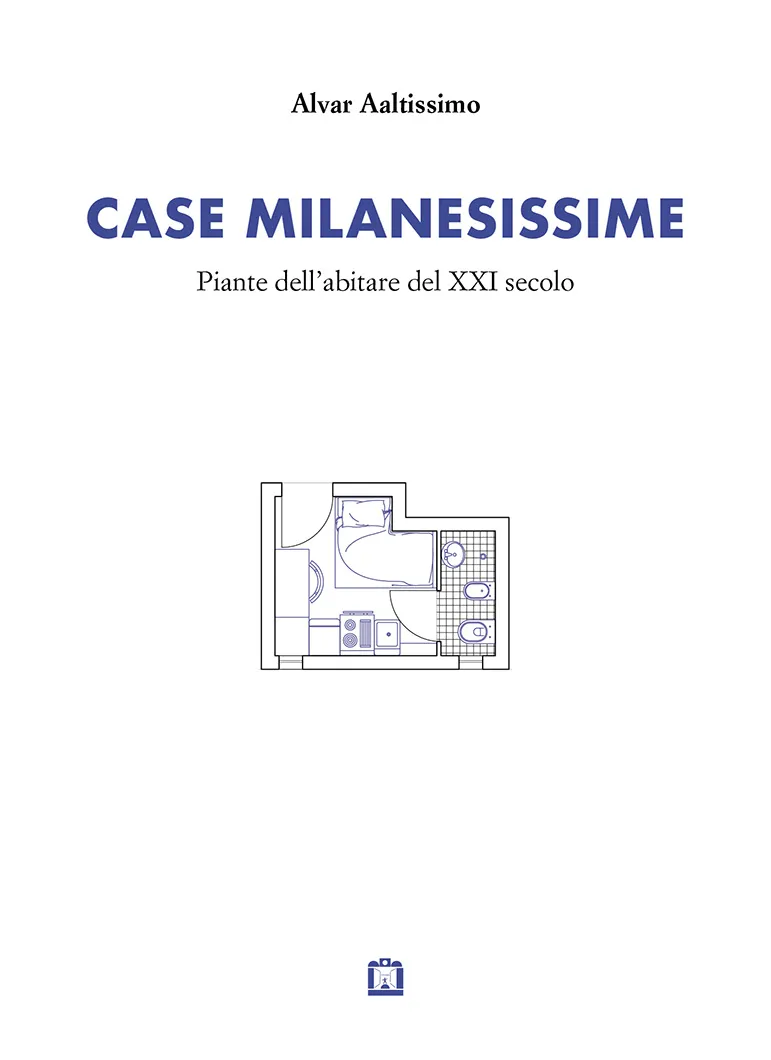

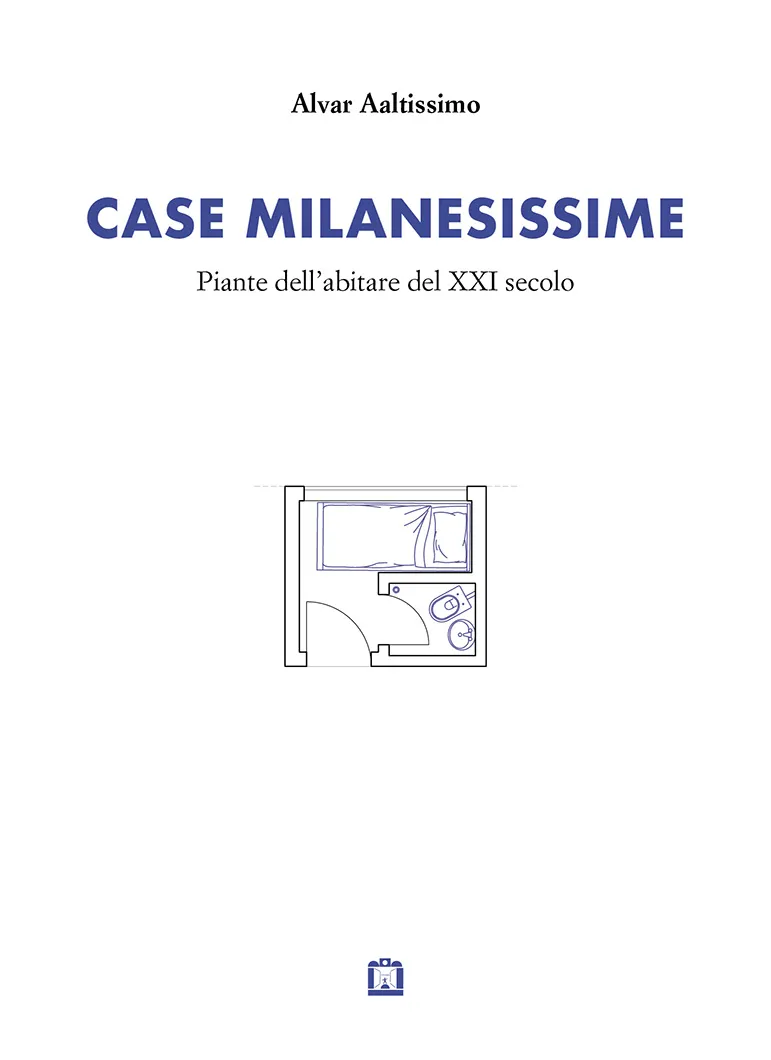

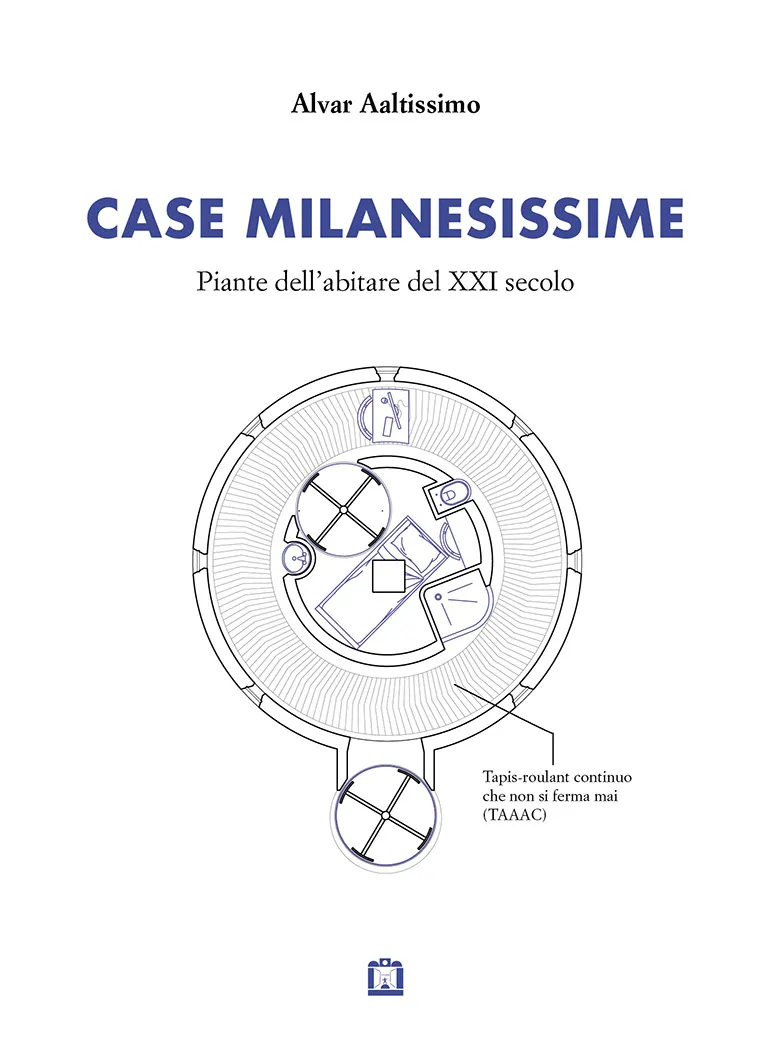

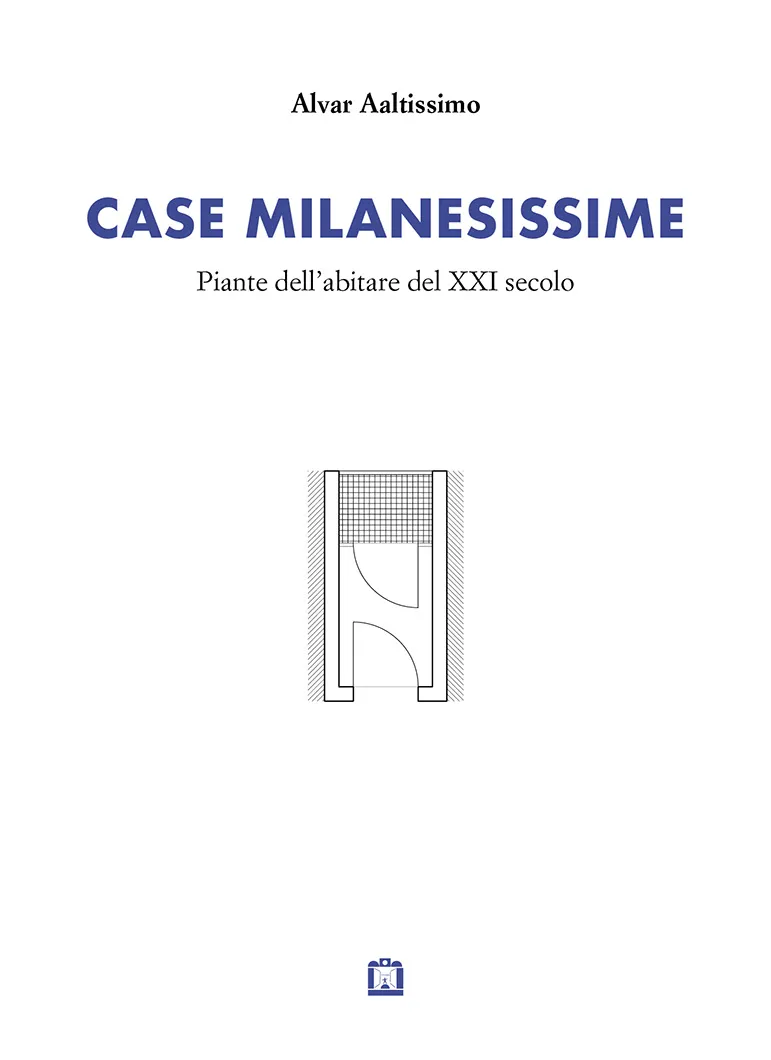

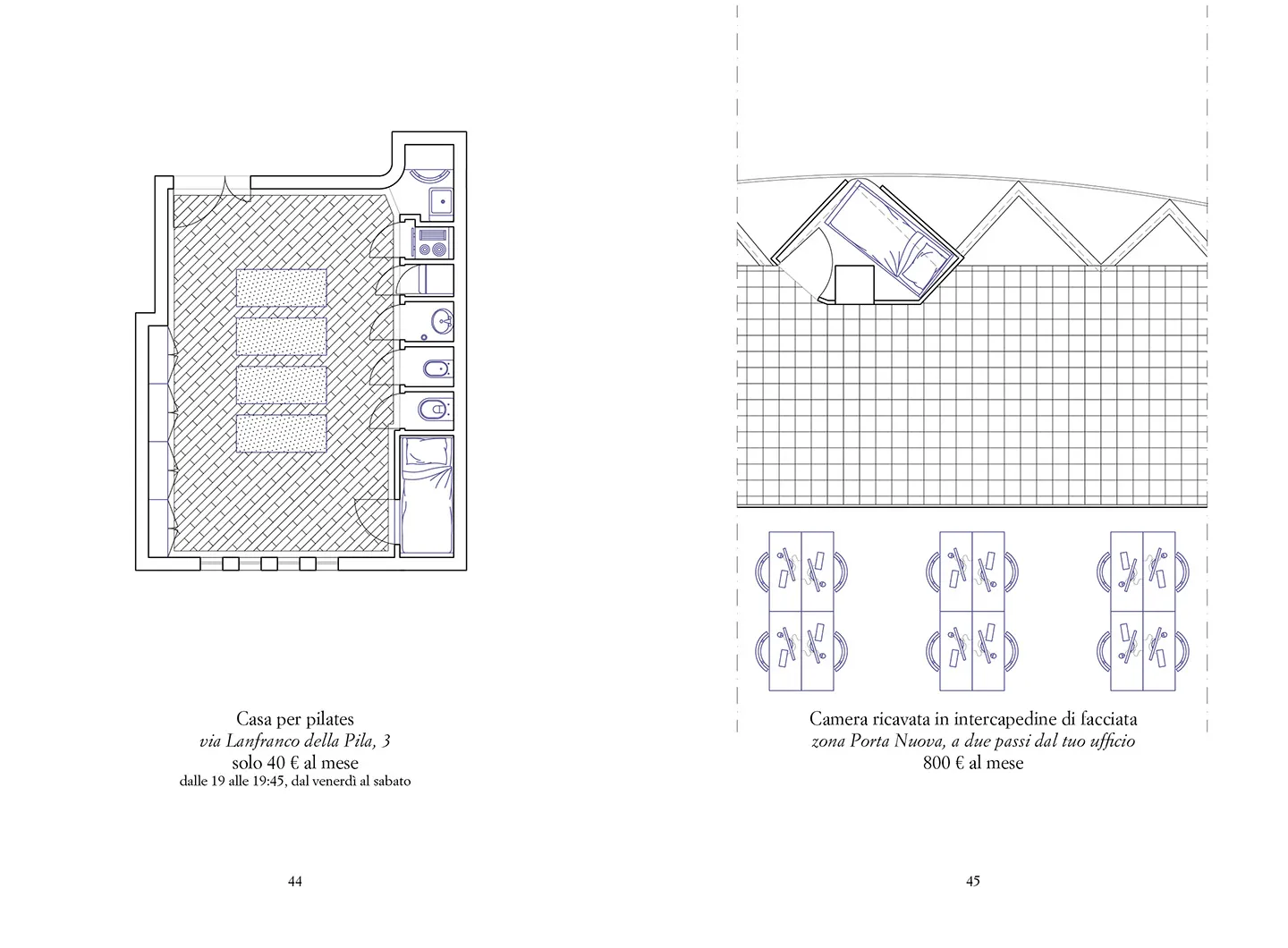

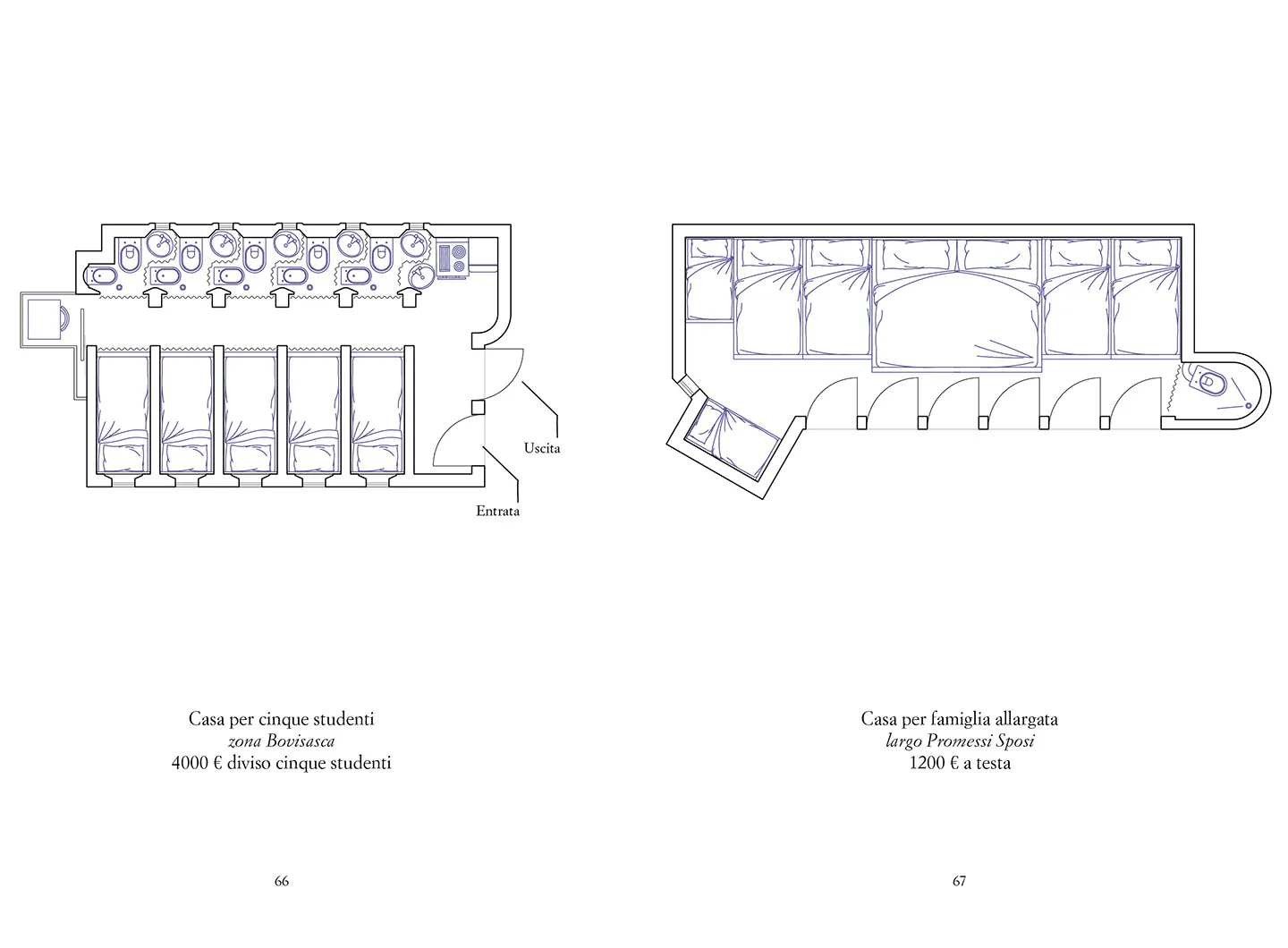

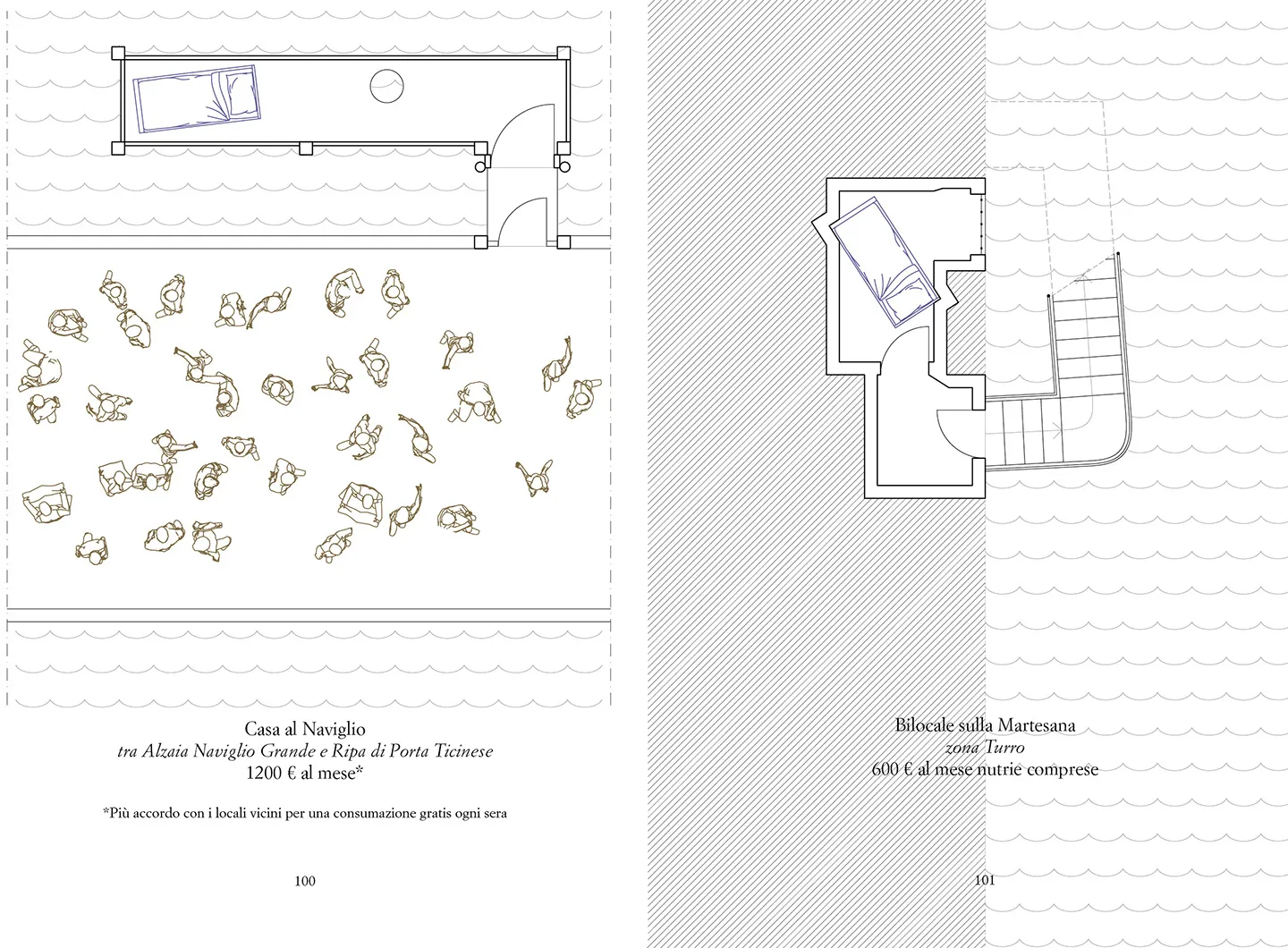

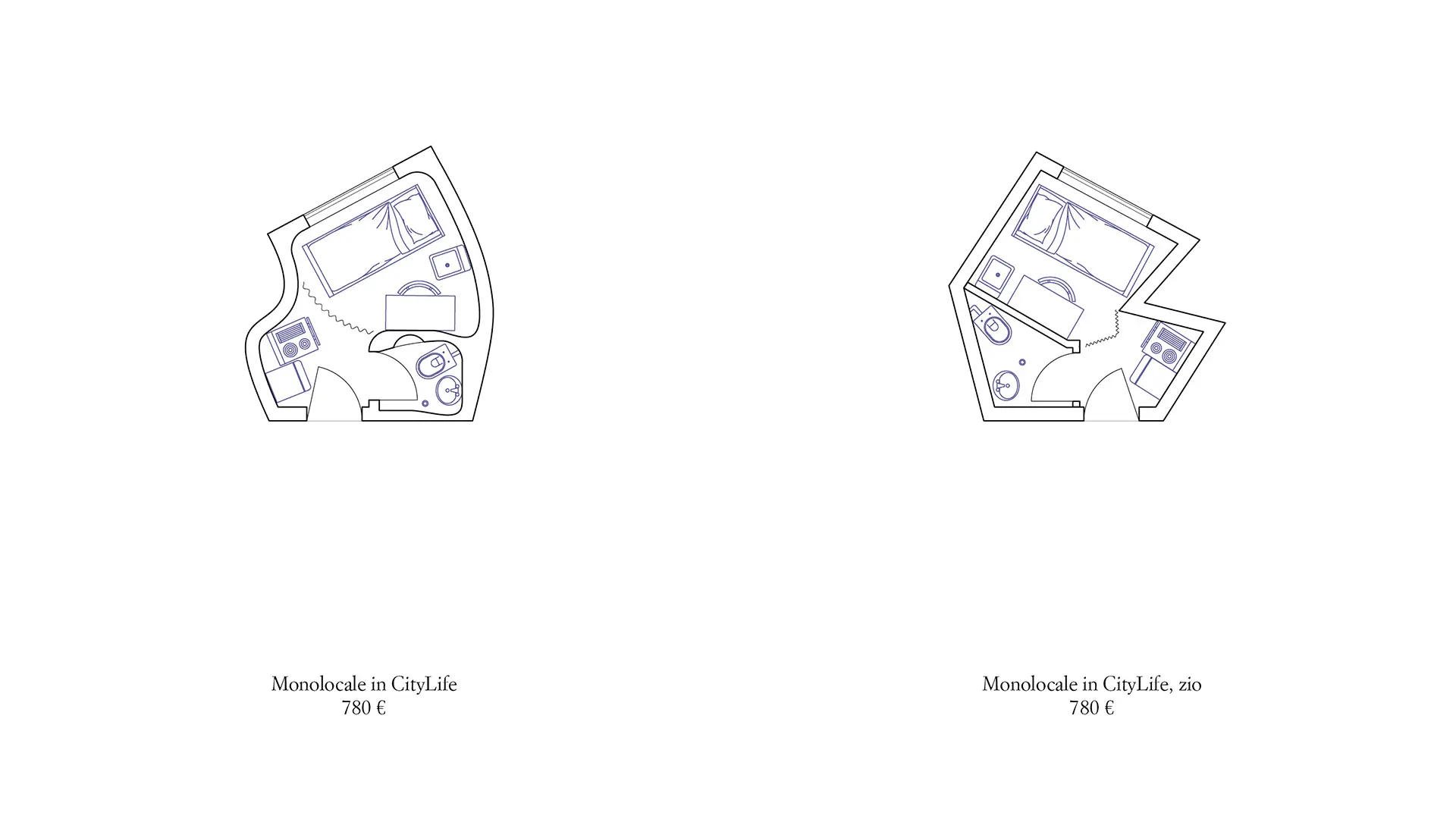

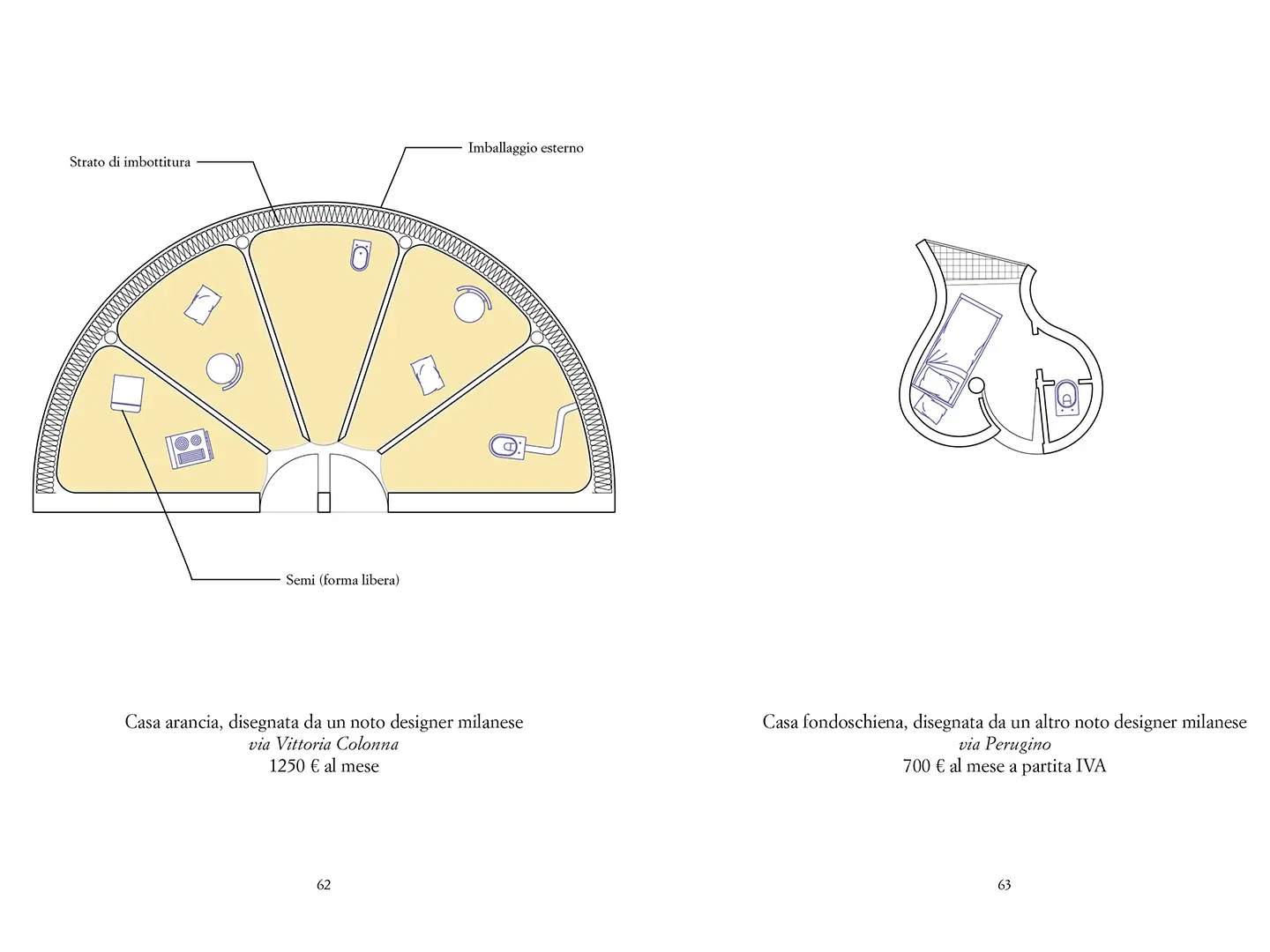

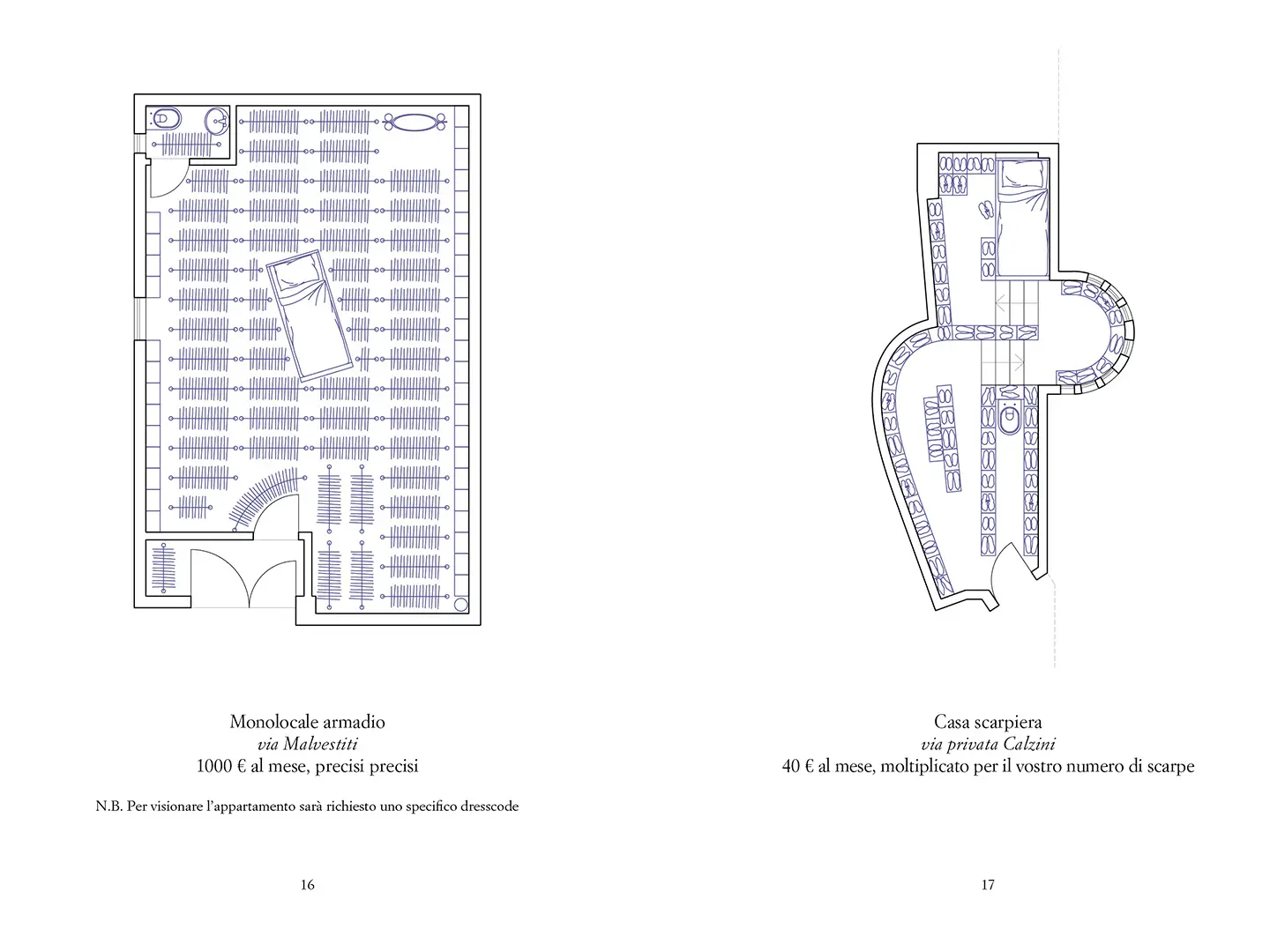

Alvar Aaltissimo casts an ironic eye over Milan’s crazy property market

Courtesy Case Milanesissime

Imaginary and surreal advertisements. Published by Corraini, with an essay by Cino Zucchi, a huge fan of the ironic social architect, a guide to looking (absurdly) for houses in Milan.

Every discipline builds its own lexicon over time; its standardised notation enables the problem of expression to be reduced to a combination of elementary parts. If the illustrated textbooks dealt out to high school pupils in order to teach them the grammar of design promised to show you how to draw a cat in five stages, the diagram in Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand’s Marche à Suivre dans la Composition d’un Projet Quelconque teaches us that, by following his method of assembly on a Cartesian grid of a classic “Lego” structure made of walls, columns, architraves, we can design “any building.” [1]

Classicism has a huge advantage over every other design method – like the manuals designed to instruct travelling salesmen on to dress “English-style” by observing some simple rules – the tie should match the socks, never mix stripes and tartan – it provides a toolkit enabling a person of average intelligence and scant talent to produce correct architecture.

It would therefore seem that – like a chess piece in which the moves it is allowed to make on the chess board are implicit within it – a verbal or graphic lexicon already implicitly contains the rules for its assembly in linguistic or construction organisms. In a not dissimilar manner to the “generative grammar” drawn up by Durand in the Precis (more or less an architectural transposition of the method advocated in the Port-Royal Grammar [2], in the Eighties William Mitchell carried out an analysis of the floor plans of Palladio’s villas in order to extrapolate the compositional methods and thus entrust the task of producing similar ones [3] to the first intelligent machines.

The lexicon of architectural floor plans – the walls sectioned in thick lines, the doors, the tiles, the sanitaryware and the burners often adhering to UNI standards – thus seem to be the most solid and objective part of a discipline, the evolutionary branches of which – like the “Cambrian explosion” documented by the fossils in the Burgess Shale [4] – have generated many bizarre, sometimes monstruous beings.

Courtesy Case Milanesissime

When sitting the State Exam for the suitability to practise as architects – Italy’s only Degree in Architecture, with its presumed intersection with just about every branch of human knowledge, is still not sufficient – every candidate knows full well that the only certain way of passing it is to be able to design an orderly plan in just a few hours with all the conventional symbols clearly marked in the right place, and to cram the drawing with written references to laws and regulations that will attest to their technical and legal competence. It is also known that every aspiring architect attempting to express any sort of pretentions to Kunstwollen or Weltanschauung in the written examination is destined to certain ruin. The State Exam primarily selects the foot soldiers and the ship’s boys of the great Construction Procedure army, checking how well they make their own beds or oil the barrels of their key weapon, the Cadastral Plan, to be officialised with the right signature and stamp. This same plan, gently embellished with hangers in the wardrobe and indeterminate plant pots on the tables and terrace, is what lends objectivity and seriousness to property details, the mainstay of stability of a social entity: the dream home – or perhaps the home we can actually afford – either rented or purchased in manageable instalments, possibly covered by a mortgage.

A few years ago, Marc Augé – the ethnographer who became famous for coining the term “non-place” later cloned in innumerable instances by newspaper hacks – attempted to explore the social, existential and aesthetic values projected by the French onto their homes as a result of careful perusal of the letting and sales property advertisements in Domaines et Chateaux. [5] Floor plans are to the photographs depicting the rooms as Computerised Axial Tomography is to possible portraits of a person: their alleged measurability and “scientific” means of representation constitutes the basis for the mutual trust that should formed by both sides in the presence of the lawyer and perhaps a technical professional, be they an architect, a construction engineer or a surveyor. A plan, rather than a photo, is often attached to legal documents attesting to the transaction. This means that the plan must depict all the properties of an apartment objectively, and provide certain parameters for the purely subjective elements that we all inevitably project onto the spaces we live in. Plans are measurable and comparable; like stuffed animals or the insects stuck through with pins in old museums, all together they could be organised into a great “natural history” of an artificial product, the home.

Joseph Goebbels stated that the intention of propaganda was not to convince people of the goodness of National-Socialist ideas, but to inform a vocabulary that, once people started adopting it, would prevent any thought diverging from that intended. The floor plan, the ideological foundation of the property world, cancels out any difference between architecture and construction, making the former a decorative option, a dazzling covering like a more or less seductive item of clothing.

So far so good, then we get to Alvar Aaltissimo and his subversive smile.

While standard forms of floor plans had temporarily reassured us about the relationship between architecture and the rest of the world (and the laws and customs that regulate it), Alvar Aaltissimo tampers with the sacred values of the discipline. He does this from the outset with his choice of pen name – or rather his pencil name - which he obtained by adding a superlative termination that throws one of his saints and masters onto the Bed of Procrustes. “Fighting the system from the inside,” would appear to be his slogan. The apparently naïve compliance with the simple language – graphic or written - of property advertisements contains a deflagrating power precisely because of its purported “realism,” an apparent normality that acts as smokescreen against explosive attacks.

In one of her videos, the former 10,000 Maniacs singer Natalie Merchant explains the artistic intentions behind the name and the contents of a song with a deliberately “banal” title – Life Is Sweet – and cites the visual artist Jenny Holzer, who reveals hidden meanings through the obsessive repetition of conventional and misused phrases taken out of context. [6]

Contrary to what the historical avantgardes often theorised, the intelligent manipulation of material deriving from shared customs often provides much deeper and long-lasting results than its reinvention.

Courtesy Case Milanesissime

Adolf Loos believed that it was not mere chance that the Romans were not capable of inventing a new order of columns, a new ornament. They were too advanced. They derived it all from the Greeks and used it for their own purposes. The Greeks wasted their powers of invention on the orders of columns, the Roman applied theirs to designing buildings. People who can solve great design problems do not spend time on new mouldings. [7] This apodictic affirmation could extend to a wide range of very different activities that all come under the same general heading. There is no need for new words to describe new ideas and sentiments, because the use of a shared language –which could even be described as “classical,” were it not likely to trigger endless debate – can avail itself of manipulation strategies which unveil the fundamental advantage: the tiniest shift in form produces a much greater and efficacious interior effect, more precise and often more disruptive than resetting the lexicon. Cezanne revolutionised art by painting oranges and bottles.

Like a cheeky child, Alvar Aaltissimo rejigs the graphic symbols that define the plan of a house by using all the classic tropes that the “Group μ” from Liege had reread in a structuralist key during the Sixties in A General Rhetoric: [8] anacoluthon, anaphora, anastrophe, aposiopesis, asyndeton, chiasmus, dialeph, ellipsis, enallage, hendidys, enjambement, epanalepsis, epiphora, hyperbaton, hyperbole, litote, homoteleuton, oximoron, paronomasia, pleonasm, polyptote, polysyndeton, prolepsi, synalepha, generalising synedoche, particularising synedoche and zeugma are all devices and figures transposed from the textual to the graphic sphere in order to create bizarre inventions; monsters that are sometimes funny, sometimes frightening or terrible like those contained in the mind and paintings of Hieronymus Bosch, composed of recognisable anatomical parts – in this case, the organs and limbs of the “house of civil habitation” – deliberately assembled along far from canonical lines.

Can an “edifying” art – not just a “constructive” one (shared with the engineer friend/enemy) but one capable of creating liveable places, embedded in the proud etymology of buildings as aedes facere - basically make houses set in stone and give lasting shape to irony and sarcasm?

In reality perhaps not – or perhaps those who have tried to do so have often built disastrous things of stone and brick. But, while we are still trying to work out whether architecture is an “autographic” or an “allographic” art and whether its tools come into the categories of “score, sketch or script” described by Nelson Goodman, [9] just as the freedom of graphic representation has, over the centuries, generated memorable utopias and dystopias – from Étienne-Louis Boullée’s Cenotaph to Newton to Archigram’s A Walking City – conceded by the apparently inoffensive satire of Alvar Aaltissimo.

Heath Robinson drew a series of humorous vignettes between 1932 and 1933 featuring devices that were as ingenious as they were imaginative but designed to help people live within the limited confines of the new urban flats. These were published in Robinson and K.R.B. Browne’s How to Live in a Flat. [10]

The drawings as a whole work more or less explicitly as a critique both astute and ferocious not just of the concept of Existenzminimum by then prevalent throughout Europe, but also of the tubular steel furniture produced under the banner of Sachlichkeit behind the only apparently neutral buffer of “functionalist design” (a few years earlier Josef Frank, in a chapter of his bizarre and prophetic speech at the Werkbund entitled Architecture as Symbol, had accused the curved tubular steel chair of not being so much a design as a vision of the world.) [11] After Stanley Kubrick’s decision to use works of Brutalist architecture as the background to Alex and his Droogs’ ultra- violence in A Clockwork Orange [12] and the dystopian lyrics in the song on the Foxtrot album by Genesis, Get ’Em Out by Friday produced during their progressive phase, [13] one could also affirm that the ideology of functionalist architecture was never really taken on board by the British lower middle classes; but Jacques Tati was just as astute and sometimes ferocious against the city and modernist homes in his two almost silent masterpieces Mon Oncle and Playtime, in which the director and actor had almost bled himself dry trying to build a gigantic life-size model of a portion of a contemporary city rechristened “Tativille.” [14]

In his recent book, Caricature Architettoniche, Gabriele Neri conducts an extremely rigorous examination of the complex relationship between the posters and proclamations on architectural theory of the last 150 years and the veritable “counterpoint” of written and graphic satire. If some of these vignettes might seem like the predictable outcome of the endemic “resistance to change” [15] that every innovation generates as an equal and contrary action, many of them manage to demolish the over-simplified assumptions underlying the regional expansion following World Wars I and II and their formal outcomes.

In a recent study into housing conditions in European cities exhibited as part of the show

At Home 20.20 at the MAXXI in Rome, the figures accompanying the photos of the living spaces of students and young professionals in Paris make one shudder: one 8 or 12 square metres space containing all the furnishings, cupboards and utensils required by a temporary inhabitant of the new metropolis.

The surreal, or perhaps hyper-real plans (in an “augmented reality” world, Alvar Aaltissimo’s drawings seem to consciously pursue the ideal of a “diminished reality”) illustrating the imaginary flats to let or buy in Milan, a city forever waiting to be admitted to the club of great European capitals, thus become an element of critical reflection on the living conditions in the city. The captions that accompany them are the key to their interpretation and constitute the means of deciphering the graphic cryptogram and the trap of an unexplored pyramid in which the sancta sanctorum (the virtual inhabitant whose physical and moral attributes must of necessity dictate the very specific characteristics of the space depicted) is forever hidden from our sight and left to our imagination.

In their Chronicles of Bustos Domecq, Jorge Luis Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares had great fun with the literary style and interpretative grids of an imaginary art critic trying to make sense of the most extreme experiments by contemporary artists; in one of the fake essays, entitled “The Flowering of an Art,” Bustos Domecq describes the gradual detachment of architectural design from the shackles of a supposed original sin, that of having to respond to a “need.” Set definitively free, the “Uninhabitables” – buildings you can’t even get into, but which can be observed from outside – can finally be regarded as “pure” architectural statements, in which the composition of the parts is regulated by autonomous matrices. [16]

It is perhaps not surprising that the apparently naïf graphic style of the plans illustrated in these pages strikingly resemble those in the graphic work of some of the most interesting young figures on the European cultural scene: Dogma, Piovenefabi, Matilde Cassani, YellowOffice/Francesca Benedetto, Salottobuono/Matteo Ghidoni, Baukuh and many more. Arthur C. Danto described the essence of this operation as “the transfiguration of the commonplace,” i.e. the more or less pronounced feeling of alienation engendered by the modern age on objects and icons of mass society. [17] In this sense, one could say that these plans cause us to look at the world of domestic architecture as if through a mirror in which the inverted or deformed image unveils and destroys the automatisms.

Through the Looking-Glass? [18] A reference to Lewis Carroll’s merciless and irreverent logic and is perhaps the only way at this point to halt the almost surreal montage of authors, thoughts and citations in this “occasional essay,” written by Alvar Aaltissimo’s greatest fan: your most affectionate Cino Zucchi.

NOTES

[1] Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand, Nouveau Précis des Leçons d’Architecture: Données à l’École Impériale Polytechnique, Fantin, Paris 1813.

[2] Antoine Arnauld and Claude Lancelot, Grammaire Générale et Raisonnée Contenant les Fondemens de l’Art de Parler, Expliqués d’une Manière Claire et Naturelle..., Pierre Le Petit, Paris 1660. General and Rational Grammar. The Port-Royal Grammar, I Volume 208 in the series Janua Linguarum. Series Minor. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110874716

[3] William J. Mitchell, The Logic of Architecture: Design, Computation, and Cognition, MIT Press, Cambridge 1990.

[4] Burgess Shale fossil-bearing deposit in Canada – which documents the so-called “Cambrian Explosion” of around 500 million years ago – which also contains the soft parts of the organisms; a number of findings, such as the Hallucigenia and the Acinocricus, defied scholars’ attempts to catalogue them for years, given that their morphology could not be traced to any known animal species.

[5] Marc Augé, Domaines et Châteaux, Seuil, Paris 1989.

[6] Natalie Merchant, VH1 Storytellers, DVD, recorded 14th September 1998 at the Manhattan Center, New York, Warner Bros Music, 2005.

[7] Adolf Loos, Architektur, in “Der Sturm”, 42 (December 1910), English translation by Shaun Whiteside, Ornament and Crime, paperback published as part of Penguin on Design, 2019

[8] Groupe μ, Rhétorique Générale, Larousse, Langue et Langage Series, Paris 1970, II edition Seuil, Collection Points, Paris 1982. A General Rhetoric, by Group μ, English translation by Paul B. Burrell and Edgar M. Slotkin. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1981

[9] Nelson Goodman, Languages of Art, Bobbs-Merrill, Indianapolis 1968. Cf. Chapter V.

[10] Heath Robinson, K. R. G. Browne, How to Live in a Flat, Hutchinson, London 1936. On the subject of one-room residential units, see also Robin Middleton, The One-Room Apartment, in “AA Files”, 4 (July 1983), pp. 60-64, Architectural Association School of Architecture.

[11] Josef Frank, Architektur als Symbol: Elemente Deutschen Neuen Bauens, A. Schroll & Co., Vienna 1930-31.

[12] There are a number of articles that describe in detail the buildings and interiors in the Greater London area used by Kubrick as settings for the film. Alex’s house is on the Southmere Estate in Thamesmead.

[13] Genesis, Foxtrot, Charisma Records, 1972, third track on the A side. “This is an announcement from Genetic Control/ It is my sad duty to inform you of a four-foot restriction on Humanoid height (…)/ It’s said now that people will be shorter in height/ They can fit twice as many in the same building site/ They say it’s alright/ Beginning with the tenants of the town of Harlow/ In the interest of humanity, they’ve been told they must go/ Told they must go-go-go-go.”

[14] Jacques Tati, Mon Oncle (1958) and Playtime (1967). Both Tati and his production company Specta Films got into serious financial difficulties when building the set for the latter. It portrayed an entire “modernist” city called Tativille. On the building of Tativille, see also the 1965 documentary Tativille-sur-Marne.

[15] Gabriele Neri, Caricature Architettoniche. Satira e Critica del Progetto Moderno, Quodlibet, Macerata 2015. Cf. Cartoon Architecture, Essay by Gabriele Neri, The Architectural Review, 16 January 2017.

[16] “The building which carries out these principles covers a rectangular plot with a frontage of six yards and a depth of something slightly under eighteen. Each of the six doors that go to make up the façade of the ground floor, communicates, at a distance of some thirty-six inches, with a similar door, and so on in succession, until at the rear of the building we arrive at the eighteenth door. Severe paneling on each side divides the six parallel systems, which all together add up to the imposing sum of one hundred and eight doors. From the windows of houses across the street, the careful observer may make out that the second floor abounds in staircases of six steps that go up and down in zigzag form; that the third floor is made up entirely of windows; the fourth, of thresholds; and the fifth and last, of floors and ceilings. The building is of crystal, a characteristic which clearly facilitates examination from the outside. So perfect is this jewel, in fact, that no one has as yet dared copy it.

And so, having come down to the present, we conclude this brief sketch of the morphological evolution of Uninhabitable Dwellings, those concentrated refreshing whiffs of pure art which do not pander to the slightest trace of utilitarianism. Inside them, nobody finds his way, takes his ease, sinks himself down into comfortable furnishings, greets the passerby from the inaccessible balcony, waves a handkerchief (or throws himself) from the upper windows. Là tout n’est qu’ordre et beauté.” Jorge Luis Borges, Adolfo Bioy Casares, Cronicas de Bustos Domecq, Editorial Losada, Buenos Aires 1967. Chronicles of Bustos Domecq. English translation by Norman Thomas di Giovanni, Allen Lane, London 1982.

[17] Arthur C. Danto, The Transfiguration of the Commonplace. A Philosophy of Art, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass. and London, 1981.

[18] Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There (1871) is the sequel to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) written by Lewis Carroll. Through the looking-glass, Alice enters a world where logic is turned on its head, in which fragments of reality and language are jumbled up to generate nonsense, or to make us reflect on their habitual mechanisms. The following is the first verse of the famous poem Jabberwocky contained in the book, crammed with portmanteau words:

“Twas brillig, and the slithy toves/ Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;/ All mimsy were the borogoves,/ And the mome raths outgrabe.”

Title: Case Milanesissime. Piante dell’Abitare del XXI secolo (Exceedingly Milanese homes: 21st Century Floor Plans)

Author: Alvar Aaltissimo

With an Essay by Cino Zucchi

Published by: Corraini Edizioni

Pages: 120

Published: 2021

Language: Italian

Stories

Stories