In partnership with MiCodmc, a selection of establishments ripe for discovery during the 63rd edition of the Salone del Mobile.Milano, from 8th to 13th April

Andrea Carson

Hailed as one of the 40 top lighting designers in the world, he brings light back into buildings and deconsecrated places to give them new identities in the name of light art.

A firm believer that Italy is the nation of beauty, Andrea Carson – 30-years-old from Novara – is fascinated by the idea of imbuing famous historic buildings with new life through the power of illumination. Founder of the only award-winning studio in Italy, he was a recipient of the 40 Under 40 Award 2020, organised by the independent British Lighting Magazine, which selects the most promising lighting designers from around the world. Along with his team at Luminum Lighting Design, set up in 2015, he has shone a new light on the creations of the architectural giants in his birth city and region, from Juvarra to Antonelli, with particular focus on sacred places, such as the Seminario Arcivescovile in Vercelli, the Duomo in Novara and the Sanctuary of the Madonna del Sasso in Boleto, on Lake Orta.

Research is essential to his professional career, always undertaken in the field of light art. His projects include Where there was Light, “hunting down” deconsecrated buildings or places in order to bestow a new identity upon them and inject new life through lighting installations. This has brought the former chapel of the IED building in Como back to life, now decked out as a textile hall and events/conference hall, as well as the old intermediate station on the Mont Blanc cable car at an altitude of 2,173 metres, transformed into the Skyway Monte Bianco museum. Innovation and valorisation are the leading characteristics of his project approach, solutions that combine the new technologies with a respect for tradition.

He has worked as a Technical Partner on projects with a number of Italian institutions (including Milan Polytechnic University, the Triennale Design Museum and the University of Naples) and works as an IOT consultant for start-ups and non-profit organisations, such as the TERA Foundation, headquartered in Novara and CERN laboratories in Geneva, where he is involved with projects for the application of IOT technologies in the field of treatment spaces for cancer patients.

It’s really hard to pinpoint a precise moment, but I really think my passion for light design began at university. I studied at the Polytechnic University of Milan, at the Milano Bovisa campus, where we were able to engage with many different aspects of the profession. I started to explore light-connected themes during courses on architectural scenography and photography, and discovered that light was a material that was both technical and artistic, with a multitude of possible uses and emotions, and I wondered what the applications for these technologies might be when it came to monuments and the artistic heritage that I learned more about during courses on restoration.

I was lucky enough to be able to experiment and enlarge on these experiences when working on an extremely interesting project in around that period, the proposal for new illumination at the Sacro Monte di Orta San Giulio (a project authored by the architect Roberto Tognetti in collaboration with Viabizzuno), an experience that opened my eyes to the incredible potential of light in channelling the poetry and providing a key to the spaces in which it was used.

Places of worship are an incredible heritage, in their multiplicity of forms and compositional differences, no matter what their scale, they manage to transmit deep emotions to the people who visit them. Light plays a major part in conveying this emotion, you only need think of Sant’Antimo Abbey in Tuscany, a place where natural light shines into the space, rendering it transcendental and timeless.

What I try to transmit in my projects, when I’m working on a religious building, is that same feeling, light shouldn’t be an invasive element, rather a veil that steals over the space, valorising its characteristics, creating a holy atmosphere, a feeling perceived internally.

I believe that when you’re dealing with a place of worship, Mies van der Rohe’s concept “less is more” ought to be applied, you need an essential light that acts as an accompanying guide, never as the protagonist when reading the space. There’s often the danger of overdoing the lighting in a place, when very often a few lighting elements suffice to emphasise particular details in order to transmit an emotion and bring out the identity of the space.

I admit it was a strange feeling receiving that recognition in such as complex period as the one we’re living through because of the COVID-19 pandemic, but it was incredibly satisfying, and it gave the whole Luminum team an energy boost for picking up again with even more determination after the crisis.

There’s still a lot of work to be done to get the role of light designer to be recognised in Italy, a figure I think now plays a crucial part in planning, equally I think it’s crucial that we find new ways to pull together and develop multidisciplinary networks in order to be successful in coordinating and making all the elements of a project work in harmony.

A message I would like to pass on is to carry on experimenting, we’re living through a time when technology allows us to create and develop light projects in a way that would have been unthinkable just a few years ago; our role is to leverage these tools as part of a vision that is exciting but also takes into account the needs and wellbeing of the people who will live in or visit a place.

Light has an extremely important influence on our lives, especially in workplaces, I think, where the wrong lighting can make things more difficult, if not harmful for people, places where often it’s the person who has to adapt to the light, when it should be exactly the reverse.

Everybody reacts to lighting in a different way, for physiological reasons, or habit or just preference, but thanks to the possibilities offered by LED lighting, along with new smart building and IOT technologies, we can now calibrate light to the precise demands of people at any stage of the day.

I’m currently collaborating on designing some innovative in-patient spaces with a cancer foundation, where we are applying an HCL concept to patient treatment areas, starting with patient needs, to come up with an IOT system that can be harnessed to customise the experience of the space according to the specific needs of the guests, so that it is the space that changes in order to improve the healing process. That’s just one of the infinite examples of how Human Centric Lighting can be applied when designing a space.

Over the last few years, I’ve been lucky enough to be able to work on collaborations with various institutions and foundations, operating in very different fields, but all focused on the desire to bring about major change in the community.

Of these, I’d like to mention the Riusiamo l’Italia Foundation in particular. We are working on a project with them in which light becomes a central element for the rehabilitation and restoration of our abandoned historic heritage, through initiatives in which lighting becomes an element that makes these spaces more accessible and activate participatory paths. The project connects with my light installation project Where there was Light, where I use light art to valorise and give a new identity to abandoned places of worship.

Dan Flavin, like James Turrel and Robert Irwin, had a profound influence on my studies, because they opened the way to a new manner of seeing and experiencing light in art.

It’s clearly hard to establish a borderline between design and art where light’s concerned. Very often when I’m working on an installation, I try to make sure that the borderline between functionality and art is as fluid as possible.

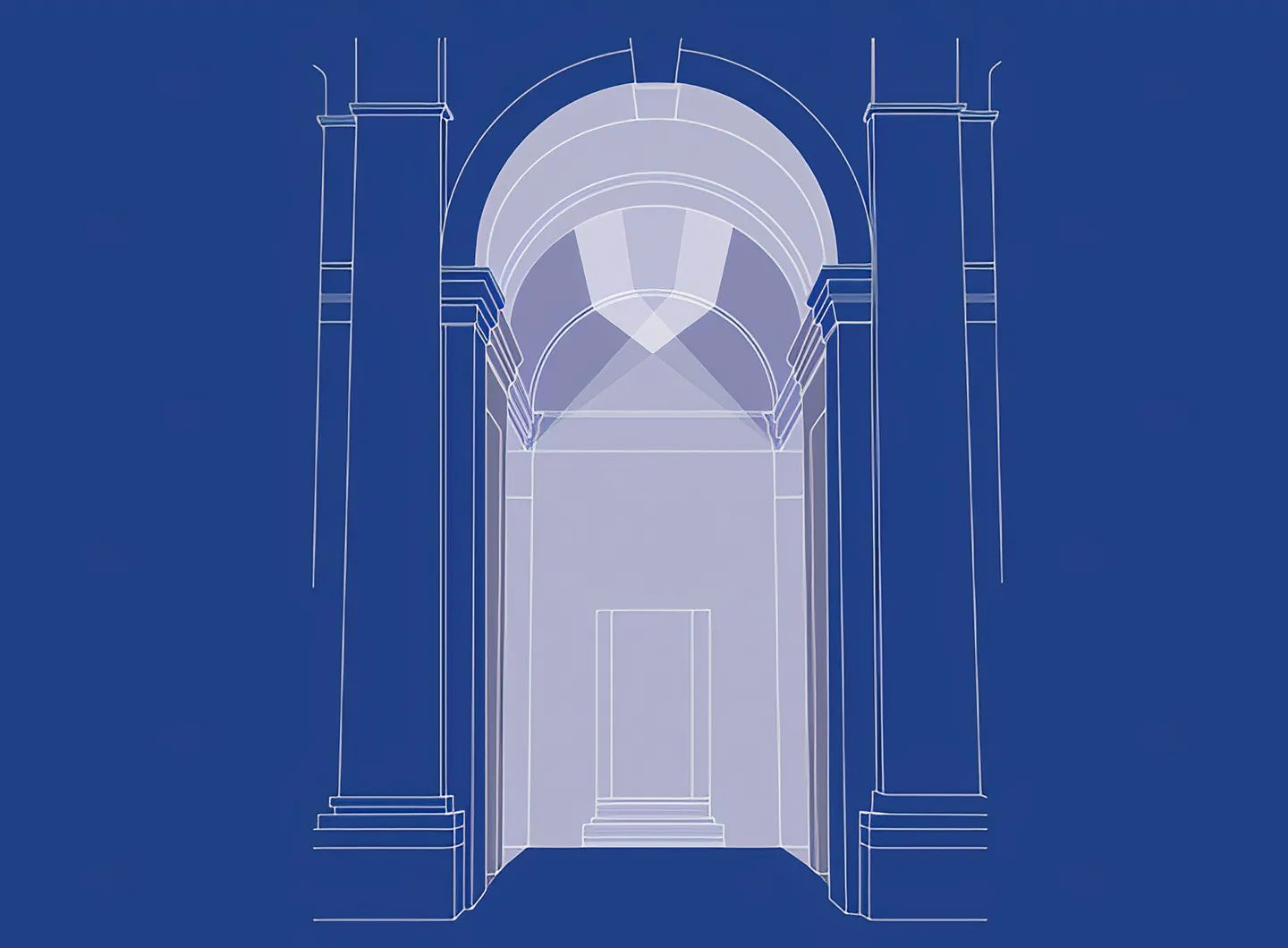

One example is the project for the portico of the Duomo, where the installation has two missions, a transit light for those going in and out of the portico and an artistic key for those looking at it from outside; it is the movement of the people that animates the space through a geometrical pattern of lights activated by timed movement sensors, the intention was to make it visible those who are approaching the four-sided portico but not to those passing through it, who become unwitting protagonists of the work, visible only to an external eye.

With the above-mentioned project Where There was Light, the light triggers a series of visions that can spark a new way of living and thinking, becoming a catalyst for seeing the space differently, and where light becomes the medium for creating new meanings and readings of spaces that are often forgotten or overlooked.

Un esempio è l’intervento per il portico del Duomo, dove l’installazione ha due anime, una luce di passaggio per chi attraversa il portico e un chiave artistica per chi lo vede dall’esterno, è il passaggio delle persone ad animare lo spazio tramite una geometria di luci che si attiva nell’attraversarlo tramite sensori temporizzati, un’opera studiata per far si che sia visibile da chi sta raggiungendo il quadriportico ma non da chi la attraversa, il quale diventa involontario protagonista dell’opera visibile solo da un occhio esterno.

Con il progetto già citato “Where there was Light” la luce innesca una serie di visioni che possano attivare un nuovo modo di vivere e pensare, diventando innesco per vedere in modo diverso lo spazio e dove la luce diventa il medium per creare nuovi significati e letture di luoghi spesso dimenticati o ignorati.

Alas, the project has remained on paper only, a proposal developed several years ago, connected with the idea of bringing design and the commercial activities of the district together, creating a link with the local churches via axes that also linked in with consolidated commercial tourist initiatives.

I strongly believe that the lighting in our cities is crying out for the sort of study that will revalue the artistic and emotional side of the night, obviously bearing legislation and safety issues in mind.

I think that when rethinking a night lighting concept it should be mandatory to look at the wider picture, not just street by street but the entire area, the thoroughfares that lead off it and connect to other districts, monuments and even commercial activities, looking for a happy medium between the harmony of the light and functionality.

As a country, we’ve got a hugely professional world of light, of art, of architecture, so setting up multidisciplinary teams when planning these interventions could bring infinite opportunities for coming up with something new. I realise it’s a challenge for a public administration, but having had the opportunity to trial it in projects for other urban areas, it’s unquestionably a vision that could be realised and which could have incredible results.

We’ve had to tackle a number of very complex challenges and locations over the last few years. When they got in touch about collaborating on the preliminary plan for the Hangar Museum in relation to the scenographic lighting, we found ourselves faced with a very particular situation, in terms of both the definition of the characteristics of the space (and the impossibility of easy access to the site), and the characteristics of the location.

I’m also thinking of the more recent Sanctuary of Barbana on the island of the same name, which can only be reached by boat from the Grado lagoon (Gorizia), these are spaces that you have an opportunity to see during the planning stage without hordes of tourists, almost in a kind of limbo, and get to grips with the logistical difficulties of a particular sort of construction site, when you see the final result the satisfaction is amazing, these are the moments when you’re glad to have been able to concretise your vision for the people who will visit that particular place.

In memoriam: David Lynch

The American director has left us at the age of 78. The Salone del Mobile.Milano had the honor of working with him during its 62nd edition, hosting his immersive installation titled “A Thinking Room”. An extraordinary journey into the depths of the mind and feelings. His vision will continue to be a source of inspiration.

Exhibitions

Exhibitions