In partnership with MiCodmc, a selection of establishments ripe for discovery during the 63rd edition of the Salone del Mobile.Milano, from 8th to 13th April

Maria Vittoria Backhaus, the photographer who chronicles the times she lives in

“I envy people who can dance.” A lengthy conversation with the photographer Maria Vittoria Backhaus, touching on Filicudi and Monferrato, the Beatles and Jacopo Benassi, analogue and digital, Gucci and Flexform. Because, what really matters, is having an idea.

Creative photographers like me don’t have much work any more. We’re not so sought-after. Now I’m trying to build a portrait of the village in Monferrato where I live, through my work. I’ve gone back to where I started: black and white reportage. The only slight difference is that it’s digitally shot. It’s a tiny place but it has some really interesting features: to do with wine and food but also with construction and the arrival of workers from abroad. I started working on the harvest first, because it was September, and then everything ground to a halt with Covid. I was also photographing all the very sweet little huts where the equipment is stored, known here as “ciabots” I’ve always liked documenting the places where I am and what’s going on. For instance I took 21 portraits of locals and, before leaving, I photographed all the objects I’d found but not taken away (a turtle shell, a top pistol, prayer cards etc.). They’re all things I left there. Curiously, when I was putting these things together I came across a picture of the Aeolian islands. Another thing I did recently was to photograph all my analogue devices and wooden plates prior to selling them. A photographer remains a photographer, even when they have no current commissions.

I’ve often been asked to photograph cars, but I just couldn’t do it! I didn’t want to; I didn’t like them. I’ve done a bit of everything, photography-wise, because I am anti-specialisation. I wasn’t interested in being a fashion or design photographer. Whatever I’ve done, I would have been mostly thinking about taking a photo. What would I like to have done? Dance! I envy people who can dance.

Yes, I’m extremely envious of people who know how to dance! There are so many other things I’d do, because naturally I want to do everything: I want to draw, embroider, cook, everything and I lose myself in these 500 different things. I am always positive I’ll finish them when I should really only take on a few projects, but I can’t help it. Another thing I’ve always done is make ugly houses beautiful. I did it at Filicudi, in Milan, and now in Monferrato. We always choose crumbling, desolate places. I really love putting them to rights. In practice what I do is create chaos. People ask me “who are you? What are you doing” and I never know how to answer them. Taking photographs, restoring houses are all part of not wanting to be defined by just one thing.

I always say that, for me, photographers are archivists. I think I’ve been an archivist. It’s what I always say, but perhaps it’s not even true. Perhaps I would have done other things better. Dancing perhaps.

You always like the most recent one best. The others are done and dusted. When I started working, fashion and design were things that weren’t anything to do with me. I wasn’t as interested in clothes or furniture as I was in chronicling my own times – even though you can’t always do so. Early in 2000 they asked me to photograph some Rolexes for Io Donna, and it turned out to be a strange photo shoot. It’s not the best, nor the one I’m fondest of, but it comes to mind from time to time because a new look had sprung up along with immigration, and we had the immigrants houses with supermarket carriers, plants, plastic flowers, religious images and, in this setting, I placed the Rolex on top of a little Indian altar. It was a story; I wasn’t really interested in the Rolex itself.

It’s more complicated with political issues. Let’s say that you can narrate your own time through images. I did another shoot that I’m really pleased with - it was of a table, shot from above with everybody involved wearing jewellery, but you couldn’t see the watches or the bracelets. What interested me was relaying the exaggerated quantities of food, the wasted food. Strangely, it was accepted.

The Beatles were almost my first subject. I’d only done one reportage with my then husband, at Palma di Montechiaro, in Sicily, when the Beatles arrived in Milan, and just in case and very enthusiastically I went along with my camera. Naturally the photo of the Beatles that everyone likes best is the one of all four of them; the one I like best, though, is the one with the riot police in front of them. They are two worlds; one image of what Italy was like. They were youngsters uprooted from Southern Italy – because there was a migration of policemen – and there they were, terrorised by people. I took part in the Student Movement in 1968. At a certain point I went to Paris with Elio Dondero and others – there’s a wonderful group photo in which I am, as always, the only woman. I went back to Paris several times because the police were making foreigners vanish and it had happened to a friend of mine. I worked for a committee that was collecting witness statements to try and find these lost people. Eventually we found him locked up in mental asylum. They gave him electric shocks and it absolutely destroyed him. It was really complicated getting him back to Italy because his father was a member of Confindustria and wanted nothing to do with it. Along with the Student Movement we put together a book of these witness statements that I transported hidden in the mudguard of my car. It was great living through that period, we were lucky. There were good times and bad, but in any case, I lived on my own and didn’t ring people to see if they wanted to come out: I went and found friends. I was out of my head, but that was how I lived and I don’t know if women still have the same freedom now to do whatever they like. I was on my own, I had a bashed-up Fiat 500 and I took off for Paris at night and always on my own. I stayed there six months without clothes, I slept on the floor at the Sorbonne, I worked on a committee and everything was normal. Then obviously I also cocked things up.

It made a massive difference, because there were women photographers then, and the best, obviously, was Letizia Battaglia, but Letizia always worked with her husband, whereas I was on my own. I had a great friend, Guido Vergani, with whom I covered regular issues but also the bandit phenomenon in Sardinia, and I loved that work. At a certain point they stopped sending me, but it was for a stupid reason: they wouldn’t pay for two different hotel rooms for the photographer and the journalist who then slept together in the rooms. Then there was the Six-Day War and sending a woman would have been unthinkable, so I got left behind. At one stage, I was fairly political and the last part of my career as a reporter I spent working for papers who sent me to shoot factories. I went by myself at night, lugging these heavy cameras, and the most interesting thing was being able to live in the factories. Back then everyone was talking about the working class but nobody knew them. I ate with them and I went into some gigantic places. I really enjoyed that period too, but inevitably the papers shut down and everything had to start all over again. I used to hang out in the Jamaica bar, Flavio Lucchini wanted me to go to L'Uomo Vogue and Casa Vogue. I said: “come and do what? I’m can’t do it.” I photographed existing things, which meant putting a photograph together. I found it difficult, but I had a go, plus I’m curious and then I liked it. For me photography was a job, I have always had to support myself. So if I couldn’t support myself through reportage, something had to change.

Moving over to digital was a disaster in some ways because I’d spent a lot of money on equipment. I had hundreds of cameras, from the Leica downwards, and I had to buy it all over again and learn from the beginning. But it wasn’t that bad for me – you had to learn it and then forget it, master the technique and then not think about it. With analogue you had to do a lot of work first, with digital you have to work a lot afterwards. I rely on digital too much when I’m making a collage, but as little as possible when I’m doing portraits. Digital is awful because if you don’t stop you get worse. If you’ve got a good idea of what you want to do, you steer clear of it. For example, when I worked for Vogue and Carla Sozzani was the editor, it was she who decided: so I only took Polaroids. You couldn’t intervene and the end result was what came out of the camera, so you had to know in advance what you wanted. It was very minimalist photography with the splendid Polaroid method. We’ve lost that side of things.

Taking a hundred snaps is a nightmare. For me choosing a proof is easy, while choosing between these digital “snapettes” drives me mad, so I try to take as few as possible. In any case, it’s the photo, not the camera that counts. I see what’s happening in the camera market, which is now aimed at dilettantes. They have to convince them that if they have a certain camera, they will certainly take marvellous photos. And they do! I’ve held workshops at which women beginners turn up with hugely expensive cameras, much more costly than mine, which they set to automatic. It doesn’t make sense. Not least because they keep the device for a year and then they change it. Everything’s on a rental basis these days. The difficult part is having the idea.

One of the projects I really enjoyed was photographing dinosaurs at Filicudi, when I took along some toys. Someone even asked me if they were alive! I like icons, small statues. Another project brought to a grinding halt by house moves and illness that I still haven’t picked up again was making miniature buildings, interiors included, and photographing them. I bought scale models of beds and I want to photograph them as if they were real interiors, in black and white, giving them a certain tone. They’re things I did for work because I built these miniatures during the 1970s and 1980s, and then took Polaroids for the purposes of advertising a shoe, for instance. The idea of faking it, of not having a set scale really pleases me.

I really like Araki. There are times when I might like LaChapelle because of something he’s done, then I like someone else … I was passionate about Jacopo Benassi after seeing one of his books, before he became famous. I think he’s really the only one on the Italian scene with that power, someone who can tell you about a world you don’t know, which is all his. He’s genuine as well as being a lovely person. I really like him. I’m not really interested in those who photograph an object for the sake of the object. They may produce spectacular photos, but there’s no story, no world behind them, they’re not part of time. But if you look at Martin Parr, you understand what America’s like. My favourite book, since childhood, which I still look at, is The Family of Man, the catalogue of the famous exhibition organised by an American state that had invited photographers to tell the story of a country.

This has got nothing to do with it, but I adopted a dog that had been in kennels for five years, and it’s been an amazing experience, because she’s a dog that has to build herself a whole new life. I watch her all the time as she tries to get to grips with it, but I also see how happy she is building and starting another life. As regards my career, I have to say that my luck has resided in the people I’ve met, the friends I’ve made. Guido Vergani, who was doing a reportage, Walter Albini, who convinced me to photograph fashion, Carla Sozzani, who was a fantastic editor, Io Donna and Vogue, which allowed me to do jewellery shoots in which you can’t see the jewels, just people eating. As a photographer working in publishing, encounters are really important. I’ve worked for many, many years with many people, Sergio Colantoni, for instance, who was the stylist – we worked on projects together and he found me the things I needed. Then there are my assistants, who I’m still close to, they were incredibly important as human relationships. They still say: “You taught me how to work,” but I didn’t teach them how to take photographs. I taught them a work method. People ask how I manage to keep working at my age – I say it’s because I deliver the photos the day before. They all laugh, but that’s the truth, it’s a discipline. The beauty of this kind of work, for someone as curious as me, is precisely that you get to know places, you get to know people.

It doesn’t work for me, but it may for some people. Not for Benassi either, I don’t think, because there’s his music, his friends, his world … For example, I kept a photographic diary at Filicudi, recording what was going on, and I asked everyone to take part, but nobody ever wanted to. It’s meant it to be an archive of life without any artistic pretensions, just a diary. Then at a certain point, I took twenty-one portraits of local people. My problem was that whenever tourists or photographers get to a holiday place, they portray the inhabitants like tramps, with chairs that are falling to bits, wearing vests, sweaty, ugly and dirty. That made me uneasy because it’s a racist image, and I wanted them all to look good, I made them wear their best clothes and took them to a lovely spot. It was really difficult to convince them because even though they knew me, they didn’t understand exactly what I was up to. I had to make them look good because those black and white, dirty photos aren’t fair. They might be great photos, technically perfect, but why don’t these people portray their friends or their lawyers like that?

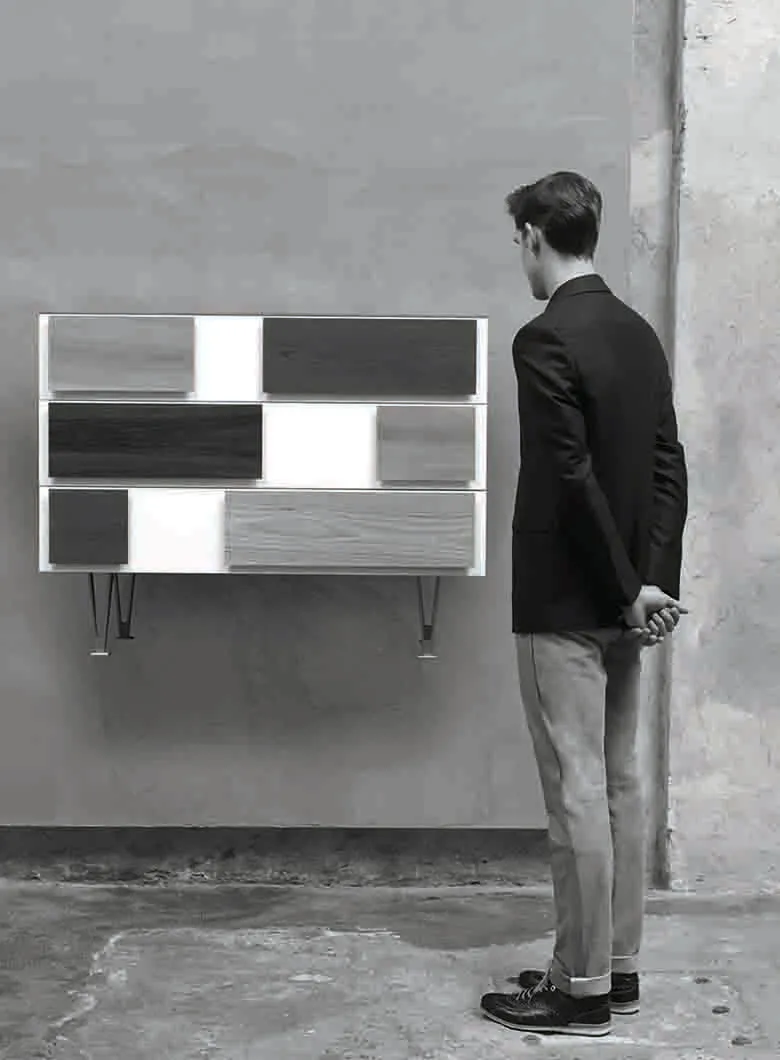

The most famous, and probably the most interesting collaboration, which lasted twenty years or maybe longer was with Flexform. At the time, there was only one kind of advertising photograph, which was a technical photo of the object, in colour, beautiful and perfect. I got a model and shot her with a film projector in black and white. Repubblica did an article on this new approach, because they were photos that broke with the established norms. I built a sort of story around the people involved - a world. Then they fired me from one day to the next! I also did shoots with Isa Vercelloni for early editions of Casa Vogue, she’s another person who lets you run with your own ideas. I’ve done very little advertising work. Apart from the fact that they never called me, they give you an egg against a background and that’s boring. There’s one who does nothing but jewellery, another does nothing but shoes – it’s a kind of nightmare! You can be brilliant, the best of all in your use of light or who knows what, but you’re constricted by that one thing. Coming from reportage, my background was completely different, and it stood me in good stead doing design and fashion and even cookery. These days newspapers have made the fundamental error of resorting to the web, to “little photos on white backgrounds.” Like on Instagram, you are only supposed to see a close-up of the object and that’s all. But it’s a huge problem, because photography will die if you’re no longer asked to tell a story.

Not really, I have to say … aside from the Gucci campaigns, they’ve all seemed pretty much the same lately. We’ve gone back to Seventies-style advertising, in which all you could see was the product. But it may be cyclical – for years Italian cinema was just pap, whereas now there’s Sorrentino, for example. Even collecting doesn’t seem to be flourishing in Italy. Then there’s also been a huge mess, people have started churning out one-offs that cost a vast amount, which I hate. I think we should produce editions of 100 and sell them for very little, so that everyone has a chance to buy them. There’s that advantage over painting. Instead, it’s the other way round – they destroy negatives … it’s madness!

Disaster! I did something, Io Contro Galimberti, [Me Against Galimberti] in which I was the commercial photographer and he was the artist. In the end I said: “you are forced to keep taking the same photo, while I am much freer,” because gallerists only want one type of photo – the kind that sells things – which you have to reproduce ad infinitum.

I based it all on the fact that I was essentially a commercial photographer who worked in publishing and was much freer than him to do what I wanted. It’s a paradox because he’ll never give up Polaroids. That’s true of many of them. I also spoke to Massimo Vitali and he had the same problem, because gallerists want beaches and, if he gets up one morning and wants to do something completely different, he can’t because it would destroy the market – it’s absurd. That’s the way you kill an artist’s creativity. It’s been a disaster in publishing and commercial advertising photography as well as art. Some photographers are paid an obscene amount, flying around in helicopters, or Porsches and Rolls Royces and taking some horrendous photos. All that mattered was the signature. Gallerists say I have no identity because I do all kinds of things, but who said artists always have to do the same things? It’s finance that’s made the rules, that’s all.

I remember during the Nineties, I went to New York, to this huge agency, Art and Commerce, and they would have taken me on straight away to do still lifes, but what happened? They said: “you have to go out to dinner every evening with the art directors” and I thought of my house in Filicudi, of my dog and I said: “why should I?” I stayed in Filicudi and photographed prickly pears and perhaps that was what I wanted to do. Because in the end, if you always take the same photos or see the same people, your life shrinks.

We left because we were getting older, it’s a place where you need good legs, it’s so tiring, but it was a wonderful place because, when we arrived there were the locals with their stories of witchcraft, we ate with them, we danced with them. Now there’s Maurizio Cattelan who parties with all the Milanese, but I’m not interested because, if you want to, you can see them in Milan. Whereas nobody lives in Filicudi anymore. They stay for a month and then off they go to Milan or somewhere else. You can’t even find anything to eat in winter. Obviously we liked being there in wintertime, out of season. We stayed for months. When you’re out of reach of social media, you can see the most amazing sunsets, the most splendid islands … in the end I’d had enough. I was interested in the relationship with the population, which became problematic when it all became the same as the mainland. I miss the way you could also be cured by witchcraft; when I was ill, everyone came along, you walked past houses and people said “come and sit down, have some pasta with us” … everyone says “I bet you really miss your house,” but I can’t miss something that’s finished and gone.

In memoriam: David Lynch

The American director has left us at the age of 78. The Salone del Mobile.Milano had the honor of working with him during its 62nd edition, hosting his immersive installation titled “A Thinking Room”. An extraordinary journey into the depths of the mind and feelings. His vision will continue to be a source of inspiration.

Stories

Stories