In partnership with MiCodmc, a selection of establishments ripe for discovery during the 63rd edition of the Salone del Mobile.Milano, from 8th to 13th April

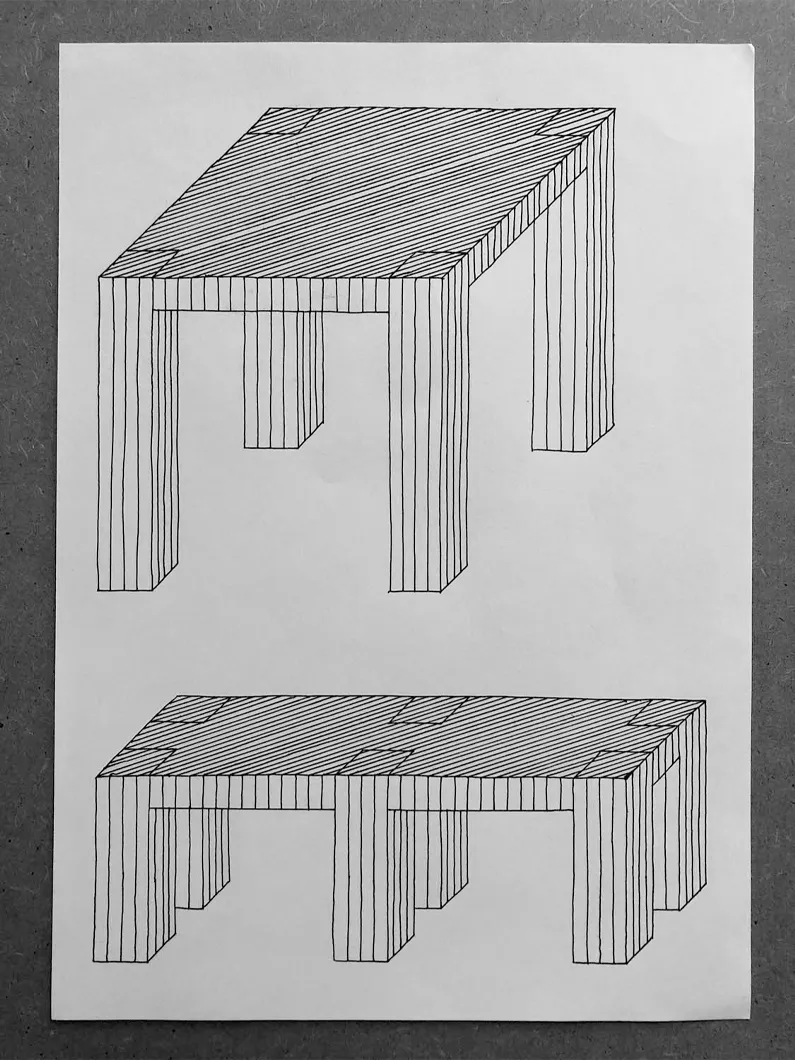

M - L - XL Studio, Heavy formal exercise, Tate Modern 2017. Photo Adrian Samson

“I like joining up the dots between the experiences I’ve had along the research paths I’ve followed.” In conversation with Marco Campardo

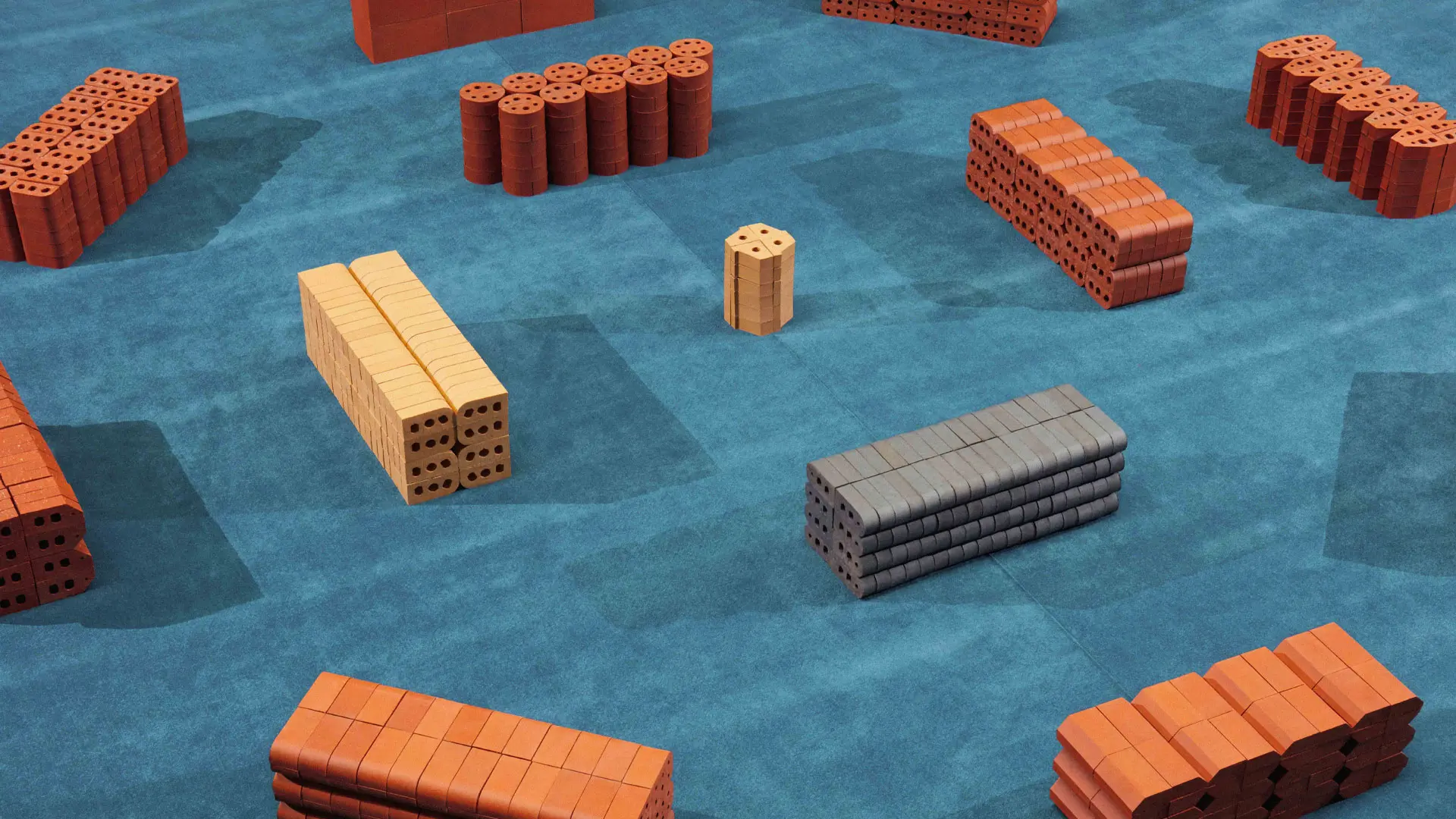

Marco Campardo is one who dodges the project preliminaries and plunges directly into the action. He likes experimenting with his hands. His pleasure in creating things at times restrains the urge to make them: “The forms are not the outcome of a design but a process.” Hailing from the Veneto, the purposeful forty-year-old designer assembles enigmatic furnishings that look like jelly or composes them by stacking iridescent metal profiles, or creates pop-up installations of clay and sugar that could disappear with a splash of water. In reality they are seats, tables, consoles, pedestals, bookcases and vases created with a machine that he built himself and made from unusual or waste materials, objects also coveted in the world of gallerists.

Since 2019 he has been living in London, where he teaches the Master’s course in Product and Furniture Design at the Istituto Marangoni and where he has just been awarded the prestigious Ralph Saltzman Prize for 2023, the second edition of the Design Museum award celebrating emerging talents. It was 2017 when Campardo, at that time with M–L-XL Studio, created an installation of 12 seats in the Turbine Hall of the Tate Modern, taking over one of the world's temples of contemporary art with a composition of handmade bricks. A solution that in one fell swoop fulfilled with simplicity the requirements of creativity, budget and avant-garde art. The designer relies on intuitive intelligence to find different forms of beauty: a speculation in design that is very close to his heart.

Marco Campardo, photo Andy Stagg for the Design Museum

I identify myself with a certain simplicity, avoiding recognizability. Everything I do is guided by the process. It doesn’t have that shape because I designed it, but because I developed a process that generates it, as happened with the Jello and Sugar Shapes collections. A method that sometimes makes me feel powerless.

I’m paralyzed by the idea of arbitrarily making an aesthetic decision with a pencil. I hardly draw anything from scratch, and I’m increasingly asked to think of a material and do what I want with it: an almost instinctive thing that is refined later. I love finding solutions to problems of work through intuitive intelligence, something not easily described. Richard Sennett (Professor of Sociology at the London School of Economics) attempted to explain it in his book Craftsman. I would like to experiment with self-generating objects, without any kind of control over form.

I get excited when what I’m observing communicates and reflects intelligence. To me this is the height of expressiveness. Everything decorative fails to move me in the least.

I use design as a speculative medium to test my materials and processes. I have an attitude towards matter that leads to aesthetic concepts of beauty lying outside the canons, in other dimensions.

Marco Campardo, Ralph Saltzman Prize 2023, photo Andy Stagg for the Design Museum

It’s a matter of affinity in a path of encounters. People help you grow and give you confidence because they understand you and grasp what you’re doing.

After graduating in Industrial Design from the IUAV in Venice I went into graphic design in a satisfactory way with collaborations and successful projects, like the ones for the MACRO – Museum of Contemporary Art in Rome, or the Venice Biennale. After that I couldn’t restrain my curiosity in the third dimension, so in 2019 I left Italy for London, to give a shape to my interests.

Graphic design is a service, while in product design you have to make the product, make it attractive to the public and be able to sell it. I feel it’s great to move into different fields, this typically Italian multidisciplinarity still exists. When you teach in England you realize there’s a specialization in the field. The humanistic approach at Italian design universities, on the other hand, provides you with a broader culture to draw on, with a mental preparation so great that you can decide how to express yourself. I studied under Michele De Lucchi and Tobia Scarpa. I remember I followed the courses held by Francesco Messina, Franco Battiato’s graphic designer. I see him as a mentor who straightened me out because I was still a prankster, but perhaps he decided to help me because he saw some glimmer in me. He had an all-round design culture that I still carry in my heart.

Marco Campardo, Elle collection, photo courtesy

I like the small dimension of design, what I call a slow burn, without exposing or distorting myself too much, which I feel is my own way. The beauty of doing things consistently, with having something to say to someone who listens, without compromising. I want to see how much intuitive intelligence I’ll be able to express in my objects.

Companies in Italy, and elsewhere, are conservative, disinclined to take risks and conduct research. We live in a historical phase when it’s not necessary to create new products. So it will be increasingly difficult for the industry to give a designer the opportunity to produce an object, which is why there will increasingly be those who will make, sell and distribute independently.

The young people I teach (Product and Furniture design at the Istituto Marangoni in London, ed.) belong to a generation not far from mine, but I feel they’re experiencing difficulty in tracing a path planned over the long term. This worries me a lot, so I always try to trigger something in their brains. I also think that we should always have the courage to pursue our dreams: you have to believe in them till the end.

The attitude to life has changed. I don’t know how far social media have contributed to this, but young people are no longer able to appreciate the present. They constantly burn it as if it were a goal to be reached in an ephemeral way, without construction, hope and foresight. Trying it as an experience is an incomprehensible concept, the meaning of the avant-garde completely ignored. I’m also very concerned about this widespread attitude to individuality.

Marco Campardo, George collection, SEEDS Gallery, London. Photo courtesy

First of all, we have to avoid promoting false myths, such as ecological solutions that are unfeasible. For instance, I’m interested in working with plastic by addressing its limits, including the problem of downcycling, of the non-recyclable recycled. The theme of sustainability is obviously present in my thoughts.

I’ll be doing a semi-personal exhibition devoted to colored resin seats in the AMO, Ambra Medda and Veronica Sommaruga’s new platform, celebrating the handmade in a kaleidoscope of objects from different ages and cultures, united through the exploration of colors, forms and materials.

Absolute. It makes me realize the direction I’ve taken is the right one, giving feedback that certainly does not feel like confirmation.

A carpet. It would be a challenge to me to raise the bar of my limits, to continue to be curious about the subject.

I have very changeable ideas.

In memoriam: David Lynch

The American director has left us at the age of 78. The Salone del Mobile.Milano had the honor of working with him during its 62nd edition, hosting his immersive installation titled “A Thinking Room”. An extraordinary journey into the depths of the mind and feelings. His vision will continue to be a source of inspiration.

Stories

Stories