In partnership with MiCodmc, a selection of establishments ripe for discovery during the 63rd edition of the Salone del Mobile.Milano, from 8th to 13th April

Interview with Fernando and Humberto Campana: creative freedom for conscious design

Humberto and Fernando Campana - Photo by Bob Wolfenson

The great solo exhibition in Rio can now be viewed in its entirety in virtual format, including the fragilities, the future, the sense of responsibility

The Campana brothers have been on the design scene for thirty-five years, instilling and spreading the need for a change of tack in everyday design practices. It’s a poetic and political project that still causes amazement and triggers reflection. It continues to improve the lives of entire communities in the favelas of Sao Paulo, by teaching women and children about design processes at the Campana Institute in Sao Paulo, which they set up in 2009. Although the pandemic stopped us from seeing their largest solo show thus far for months on end, it failed to halt their creativity and their initiatives.

One of these was to start breathing new life into the family farm – where they’ve planted more than 16,000 autochthonous plants since 2000, in order to prevent their extinction – with the first 3 of 12 totally innovative “green pavilions” in which visitors can commune with nature, art, design and architecture. A sort of environmental school for educating people, a school for manual traditions. They talked to us about it and a great deal more besides.

The Dois Irmãos (Two Brothers) bench from the Transwood collection marks the 35th anniversary of the Campanas’ careers and evokes values they hold dear: unity and partnership. Photo ©Eduardo Delfim

The work of Estudio Campana has always highlighted the importance of sustainable design from a natural and a human point of view. Right from the start, we have praised and employed traditional handcrafting techniques, which automatically means giving work to independent and small businesses in Brazil and abroad. Repurposing materials has always been one of our hallmarks, even before upcycling or recycling became a hot topic. Today, we continue to evolve, by making sure our sources are certified and doing their very best to minimise or avoid waste and pollution, equally we keep an eye on new sustainable materials that are being developed. In the end, all these mechanisms ensure that our business feed off each other, creating a healthy production cycle that holds people and the environment uppermost in the long run.

People are much more connected to their possessions these days. There’s a relationship of affection towards them, a need for every object to have an underlying meaning. From the moment we offer people a piece that has been crafted by many hands, made with care, expertise and purpose, it becomes more attractive than one that is just another object. This awareness of the true value of a sustainable piece directly reflects where each of us stands as designers and consumers. We are all responsible for what we purchase, so why not own something that sends a positive message and supports best practices?

An Estudio Campana icon, the Paraiba Chair of 2006 uses traditional dolls handmade by a community in north-east Brazil. Photo ©Luis Calazans

All workshop activities with kids have now been halted due to the pandemic, but we continue to liaise with NGOs, institutions and business partners so we can expand our activities as soon as possible. Essentially, Instituto Campana seeks to transform disadvantaged people’s lives (children and adults) through design, giving them new perspectives by teaching or honing their existing skills. I’m [says Humberto, Ed.] talking about individuals and communities that experience hardship every day and are unable to see any prospects in their lives (kids from broken families, former prisoners and addicts etc.). “Building a life with my hands" was always my motto, so I try to show them how they can do the same and take pride in what they can achieve with these new skills. We often purchase the pieces produced in these workshops, sell them through the institute, museum shops and fairs, and return the profits to them. It’s very rewarding to see the transformation, the moment they realise they can make a living from something they have made themselves within a community setting.

We also see this in brands looking to work with us, as it adds to the social responsibility that corporations want to take on, precisely because consumers expect them to play an active part in that field. It’s great for us – the more resources we have from partners that genuinely share our views, the more people we can reach. Aside from workshops, a new project we are very excited about is the new outdoor development Fernando and I started at our family farm in Brotas, in the state of Sao Paulo. We have planted 16,000 trees since the 2000s in a bid to restore the native species lost through hundreds of years of farming, and which we now want to integrate with art pavilions open to the public. Sculpture gardens and contemplation spaces that bring people closer to nature and art.

A soft tube of covered polyurethane, 120 metres long, woven into a nest shape. It’s a historic Campana piece, featured in the catalogue of Edra - the Italian company with which they have produced most of their projects, right from the outset.

I think the main message is preservation. Preservation of vernacular skills, preservation of nature, preservation of our memory, our legacy. Brazil has a chronic problem in that people forget their history far too quickly. Our current government is sad proof of this. We are trying to do our bit by giving back to society and nature, and the best way of achieving this is through education. All our items carry a little bit of this message, but if I had to pick a particular one it would be our Paraíba chair, because it was during a partnership with this community of artisans in the northeast of Brazil that we realised the impact our design choices really had on people. That was the first seed that gave root to the foundation of the Campana Institute.

Not at all. Limited editions are one of our niche markets, but there are many others, which are quite affordable. Regardless of brands or prices, what really matters is that we employ 20 people, and many others indirectly. Even during the pandemic, we managed to keep everybody on board. Also, a portion of the profits goes back to the institute, so one way or the other, every project is fuelling the wellbeing of people in general.

Dated 2007, it’s called the Trans Chair and is made of wicker and various found rubber and plastic objects. It symbolises the victory of nature over the dominance of plastic and all that is artificial. Photo ©Andrew Garn

From my understanding, fragility is when you are unable to cope or feel powerless towards the unexpected challenges of life. This worldwide Covid-19 pandemic certainly brought all of humanity to the same level of vulnerability, exposing this state in most of us, while others found an opportunity to quickly change the status quo. We address it through our design work by translating these fears and darkness into objects by giving them a soul and re-signifying them. A chair is much more than its function or shape, it carries a message. You can see this in our “Hybridism” collection, a dystopian narrative of the fragility of humanity when faced with the relentless power of nature. Or, most recently, “Cativeiro” (captivity), on display at the Pompidou-Metz exhibition “Face to Face Arcimboldo”, where we address the politics of humanity imprisoning itself through omnipresent technologic monitoring. Narrative design is certainly a great tool to bring awareness to current subjects, and awareness is the first step to empower us and deal with the unexpected.

The exhibition was sparked by an invitation from MAM Rio, which gave us an opportunity to fulfil our long-term dream of showing our work in this iconic venue dedicated to art, design and architecture. As we started working on it, it felt a bit like Werner Herzog’s film Fitzcarraldo, in which the main character is determined to drag a steamboat over a steep hill. The entire process was very challenging and required a lot of team effort, but we certainly learned a great deal from it. We worked with a local NGO in Rio to develop a sustainable set design that could be repurposed post-exhibition. We involved the community in building the installations. We reached out to friends who collaborated on the book that was recently published. It was a celebration in which we brought together everyone and everything that we hold true to our vision, which took us along this path and to this stage in our career. Instituto Campana also played a vital role in liaising with collectors, handling pieces from our archives and underpinning the educational side of the exhibition.

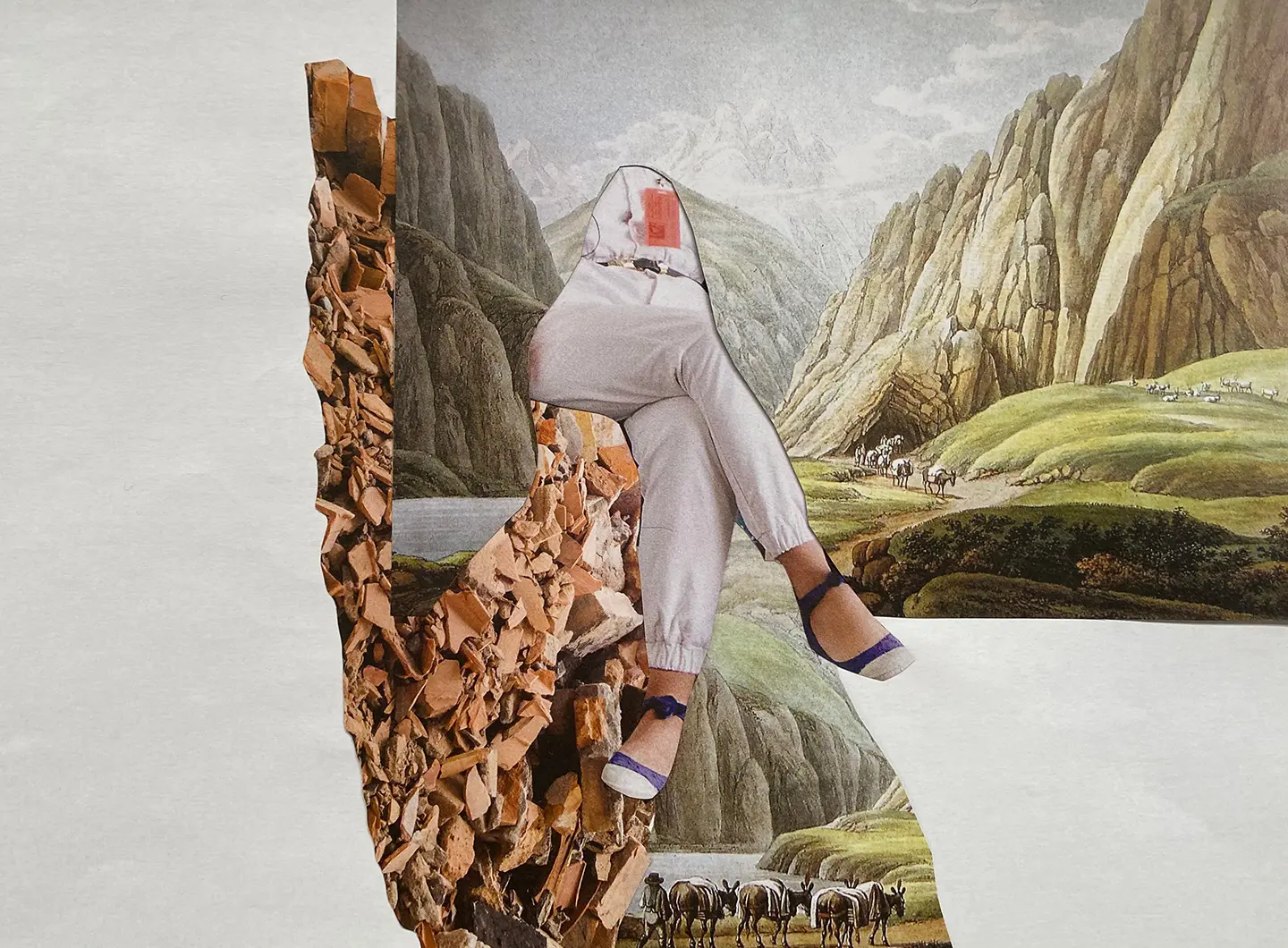

One of the collages created by Humberto Campana during the first lockdown and included in the digital exhibition At HOME 20.20 on the MAXXI Rome Instagram channel. Photo ©Studio Campana

The way the themed rooms were arranged was decided by the curator of the exhibition. Francesca Alfano Miglietti drew a parallel between our work and the universal values and conditions of humanity. She developed a very interesting way of selecting and grouping artworks that identified with each of these themes through the unspoken stories carried by each piece, in a way that everybody can relate to. Space-wise, it was a wonderful solution as it wasn’t as if each room was closed off or separated from the others. Instead, visitors could transition naturally and seamlessly from one to the other by walking through a forest of piassava stalks [a raffia-like vegetable fibre, Ed.], rather in the way that love can overlay our dreams and thoughts or secrets. There were also sound cues coming from inside these stalks, where we could listen to our voices reciting some poetic statements written by Francesca. It was all very beautiful and surreal, whilst also transmitting a powerful warning about the destruction of our environment.

The Noah bench from the Hybridism [controllare per favore] collection is made of cast bronze and woven strips of fabric. It is a call for reflection on animal conservation. Courtesy Estudio Campana. Photo ©Fernando Laszlo

I believe the pandemic destroyed an entire capitalist system in terms of employment and the workplace, when we were suddenly forced to spend a lot more time at home. That led to greater investment in domestic items that increased the comfort and flexibility of our spaces. I believe this shift in the concept of home will remain even after things return to some level of normality. The fact that we no longer have to catch a plane or spend hours in traffic to get to important meetings, when we can have video calls whilst helping to reduce our carbon footprint, will still be valid. It’s a positive outlook and I think this is definitely an important design issue for the present and for the future.

Mickey Mouse brings back childhood memories for us. We grew up watching his cartoons and always loved his wit and ability to disentangle himself from tricky situations. He is a fun character that became this timeless pop icon, so we chose the “vintage” version of Mickey for its appeal to all generations.

Pop icon Mickey Mouse impressed into a ping pong table, for Walt Disney, using the ancient mosaic technique. A sophisticated contrast. Each table takes 300 hours to create. It comes in a 25-piece limited edition.

Exhibitions

Exhibitions