In partnership with MiCodmc, a selection of establishments ripe for discovery during the 63rd edition of the Salone del Mobile.Milano, from 8th to 13th April

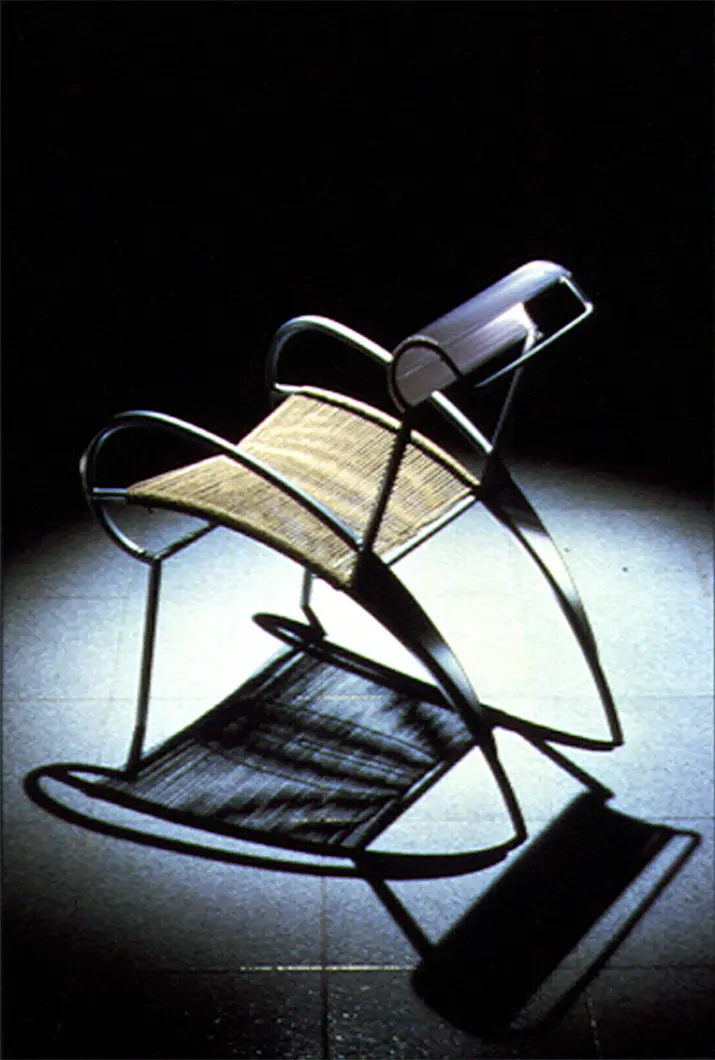

Massimo Iosa Ghini, Garden City, Bologna

After a debut in the avant-garde, the Bolognese architect has made the synthesis between pragmatism and welcoming the cornerstone of his professional language. Without ever renouncing the call of a project made not for pleasure, but to restore pleasure

Forty years in a job are something of milestone, an opportunity to look back on the origins of and messages carried by one’s own work, and to look to the future with determined optimism, picking up and carrying forward existing signals towards new goals. Having come to prominence on the design scene during the Eighties, a theorist of the satisfaction of soft, welcoming lines, Massimo Iosa Ghini helms and coordinates projects all over the world with his practice Iosa Ghini Associati. We chatted about sustainability, leaps of scale and an irreducible tendency towards Italianness, a matrix of resources and unpredictable solutions.

Italian designers – I use the category of Italianness despite its obvious genericity – have in common the idea of innovating, experimenting. Without being anti-scientific, we favour the empirical creative method: a common attribute that is part of our national character and tradition. My beginnings are in line with this stance, the inclination to not accept the status quo, but to forge paths of innovation and creativity. The movementist part, which is also very Italian, I’m thinking about Futurism here, stemmed from a desire to go back to finding new avenues, strategies, and solutions and also to use design as an expressive medium charged with meaning as well as being a product.

We certainly have an ability to identify new things: it’s a cultural sensitivity that we possess that’s owed to our rich past and we have developed captors that enable us to identify responses and be the first to understand where human/social evolution is heading. If we apply this approach to the production world, we note that new things and elements are proposed in every period that aren’t entirely indispensable, experimental in fact. Within that mass, however, there are important responses that we need to identify. This is the way we operate; by innovating even by generating waste. Creating and then realising that within that creation there were important elements capable of generating new developments, while others lacked sufficient novelty value.

I was trained to have this broad vision, the concept of the broad spectrum that we always return to - “from the spoon to the city” to quote Ernesto Nathan Rogers - a vital predisposition that again derives from the Renaissance and enables us to look at things in a general, open sense. This a-specialist vision – as Alessandro Mendini used to say: “we are horizontal, not vertical architects” – gives society the advantage of being able to innovate in a more democratic manner, taking everybody into account, not just one person in particular.

We’re seeing a pivotal awareness of just how fundamental the issue of sustainability is. Sustainability today is, of necessity, a broad strategy: in 2006 I tried to describe it in a book entitled Sostenibile ma Bello [Sustainable but Beautiful], intended to be a stance embracing the issue in order to define and control it. Sustainability is extremely multifaceted, and it is also a medicine that we have to swallow, because we have realised that we can no longer think of moving forward without again questioning the concept of growth.

The technical, Latouchian vision [as in Serge Latouche, theorist of happy degrowth, Ed.] recommends that we cut environmental impact which, to be honest, is obvious now, starting from the assumption that if we curb emissions the Earth will rebalance. I think the point is how we curb them. What we need are intelligent strategies, not superficial but effective ones, that will allow us to live in a declining context in a happy way, that is sustainable not just for the planet but also for us in our daily lives made up of the happiness of living.

An optimist, absolutely. The reaction is there. As Italians, even if I insist on the generic nature of the term, we will be capable of providing extraordinary answers, as we’ve done in design for some time. I believe that our engrained culture allows us to come up with a response that is difficult to predict.

The project is a commission based around the idea of creating a residential space that is a synthesis of all the assumptions around sustainability, again based on the idea of creating places where people can live well – because, despite the fact that I might appear to be a Calvinist, I am a fundamental hedonist. We have created one-and two-family homes, with a fairly dense proximity fabric and no verticalisation, favouring the architectural typologies of the area such as double-pitched roofs and creating greenhouse spaces of around 10-20 square metres for each house, into which vegetable gardens can be introduced, following the city’s tradition of urban gardens. We also built in sustainability technology, including wind power for a small school, along with a very high ratio of green space, twice as much as the city average. There is no need for cars in the Green Village - they are left outside the perimeter so residents can access their homes on foot or by car sharing.

Nature has to be respected. The point is that instead of forcing it, we should go along with it, with strategies that do not attempt to change it – we have to go with its flow. We can do this if we truly get to grips with it, if we manage to integrate it. Overcoming the old idea of nature as decoration, and balancing it with the artificial part.

In memoriam: David Lynch

The American director has left us at the age of 78. The Salone del Mobile.Milano had the honor of working with him during its 62nd edition, hosting his immersive installation titled “A Thinking Room”. An extraordinary journey into the depths of the mind and feelings. His vision will continue to be a source of inspiration.

Sustainability

Sustainability