In partnership with MiCodmc, a selection of establishments ripe for discovery during the 63rd edition of the Salone del Mobile.Milano, from 8th to 13th April

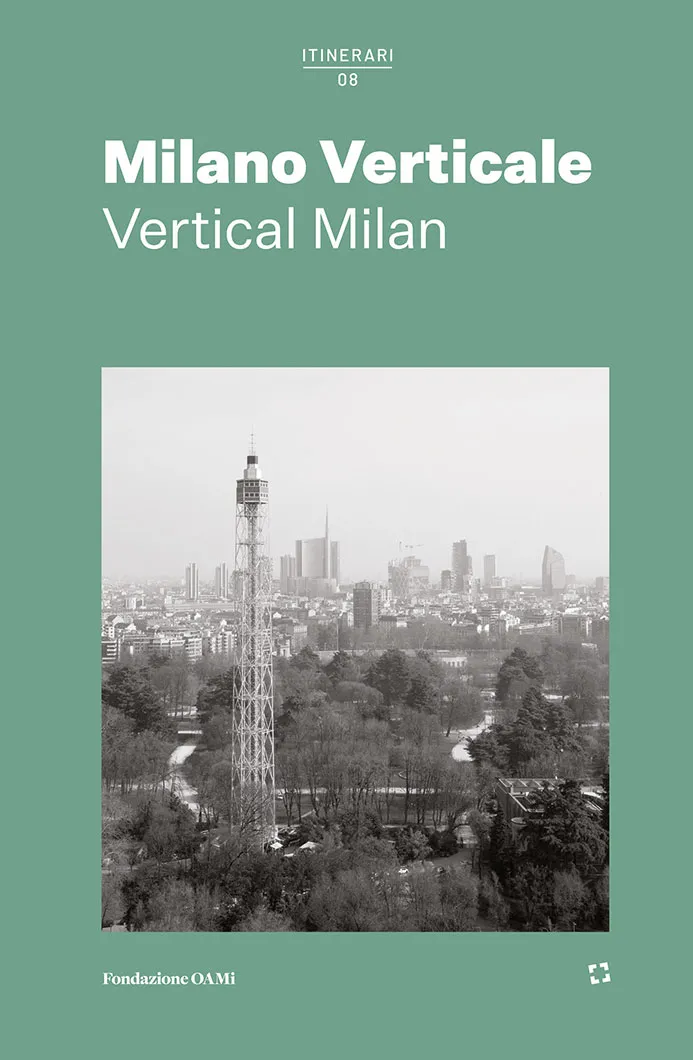

Milano Verticale Ph Giovanna Silva

The eighth volume in the OAMi Foundation’s Itinerari di Architettura Milanese series traces the history of Milan’s skyscrapers, exploring the meaning of vertical development from the 20th century to today.

What might seem just a simple guide to Milan’s tower blocks – the eighth in the series Itinerari di Architettura Milanese published by the PPC Milan Association of Architects (OAMi Foundation) – in fact contains a critical reflection on how the city’s new skyscrapers are not expressions of local identity but of global enterprise capitals and a depersonalised, anonymous and corporate clientele. In his introduction to the book, Fulvio Irace writes “The Milanese tower blocks of the 21st century rarely appear to be the fruit of much research and are more often than not an expression of a generic city underpinned by the programmes and protocols of an impersonal market demanding easy and therefore immediately attractive symbols. Not surprisingly, aside from a few tentative local partnerships, the protagonists of this new attempt to reach for the sky are well versed in a tried and tested international formula, the only way of guaranteeing productive investment efficiency, speed of design and execution and bland, globally diffuse taste.”

Milano Verticale Ph Giovanna Silva

While the concept of modernity has long been associated with vertical development as exemplified by Manhattan, and in this sense Milan has been emblematic among the Italian cities, these days the concept of a modern city takes in other factors, such as the environmental crisis, attention to quality of life and the desire to build a new relationship between urban space and natural context. The need to establish a powerful bond between the skyscrapers and what lies at their feet emerges from an interview between the architect Carles Muro, a member of the Itinerari di Architettura Milanese scientific committee and Jacques Herzog who, on the subject of Manhattan, compared the skyscrapers with tall trees and all the public and commercial activities underpinning the city with a thriving undergrowth. That is not the case in Milan. “I think tall buildings in Milan are somewhat equivocal – they’re built on a sort of artificial platform and they don’t seem to be able to be really rooted in the ground,” says Herzog. “We have to be aware of how tall buildings connect with the ground and what they generate at street level – are they accessible or do they create a sort of isolation?” Hong Kong is an exemplary case where, despite the presence of extremely tall buildings and a lack of public spaces, the vegetation is abundant and the ground floors and lobbies of private buildings have been turned into public spaces people can walk through or pause for a while.

Milano Verticale Ph Giovanna Silva

Milan hasn’t always been distinguished by its impersonality. The early skyscrapers, from those that first shot up in the 1930s (Alessando Rimini’s Snia Viscosa building in Corso Matteotti and Mario Bacciocchi’s Locatelli building in Piazza della Repubblica) right up to the 1950s (Gio Ponti’s Pirelli skyscraper at the Central Station; the Breda building by Luigi Mattioni, Eugenio and Ermenegildo Soncini in Piazza della Repubblica; BBPR’s Velasca building in Missori; Mattioni’s buildings in Piazza Diaz, Via Turati, Largo V Alpini and Via Fara; Melchiorre Bega’s Galfa building; Portaluppi’s Biancamano building; and the municipal technical services building by Gandolfi, Bazzoni, Fantino and Putelli in Melchiorre Gioia), they all came into being during a “fervid period of projects that presupposed a shared concept of the city: a last ditch attempt to share a common language notwithstanding the inevitable expressions of individual sensibilities,” as Fulvio Irace put it.

Milano Verticale Ph Giovanna Silva

The central chapters of the book are given over to a detailed discussion of some of these skyscrapers, photographed by Giovanna Silva, starting with those that were bold enough to get past the Madonnina (a law imposed during the Fascist era that banned any building from being taller than the highest of the cathedral spires), and move on to more recent examples in the former industrial areas of Porta Garibaldi and City-Life, all designed post-2010 and which earned Milan the title of Vertical City with its record seven of the ten tallest buildings in Italy. Controversial as they may be, these projects have the merit of having sparked debate on urban regeneration, public and green space policy. The focus should be on the foot of buildings, rather than on their verticality, in a bid to make them attractive and alive and capable of exerting a magnetic force like that achieved by the Prada Foundation – as Jacques Herzog remarked. Despite not being particularly visible from afar, the Foundation has become a new urban landmark, transforming a former industrial site into a new and extraordinary space, truly capable of attracting both citizens and investment.

Title: Milano Verticale

Curated by: S. Galateo

Drawing by: Studio Folder

Published by: Fondazione OAMi

Published: 2021

Pages: 66

Language: Italian and english

Stories

Stories