In partnership with MiCodmc, a selection of establishments ripe for discovery during the 63rd edition of the Salone del Mobile.Milano, from 8th to 13th April

The Noguchi Museum: the home of a nomadic modernist

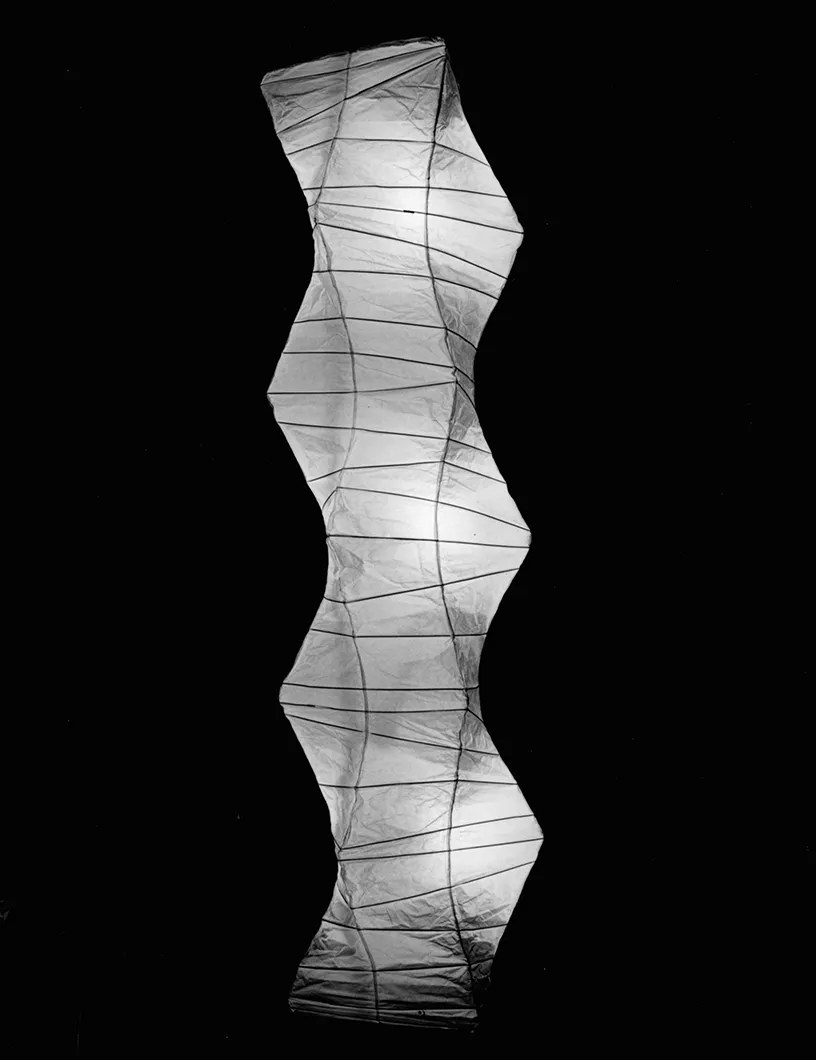

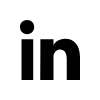

Isamu Noguchi, Akari UF3-Q, UF4-33N, and UF3-S. The Noguchi Museum Archives, 03565. © The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / Artists Rights Society

In 1961, Isamu Noguchi moved from Greenwich Village to Long Island City, where he began building a museum to exhibit his works and, most importantly, fully express his vision

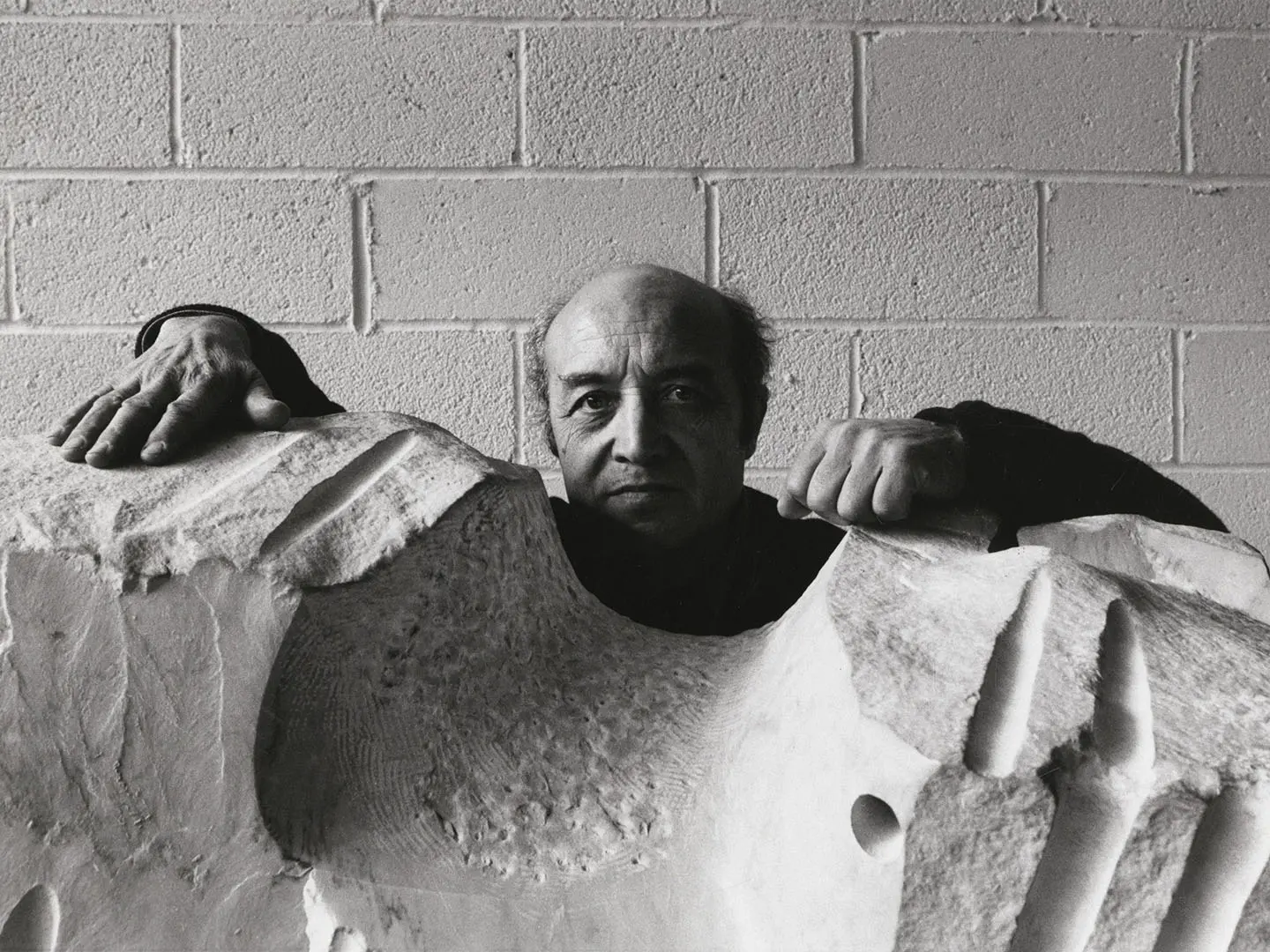

Updated on 10 July 2023. Seemingly elusive, some artists abandon the field of identity and establish themselves in a different, fascinating and necessary land. Isamu Noguchi, a Japanese-American sculptor, architect, landscape architect, designer, and set designer, is just one such artist, who worked in every possible material, from paper to bone and cement, and travelled and lived all over the world. He set up a number of different studios in the areas key to his biography and inspiration – the USA, the Mediterranean, and Japan – only to unceasingly self-displace to explore, synthesize and deterritorialize, as Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari would have it. The displacement was, however, inversely proportional in distance to how decisive the move was for his creative and existential parabola, when in 1961 Noguchi moved his studio from frenetic Greenwich Village, Manhattan’s artistic and bohemian centre, where the Sixties counterculture was getting into gear, to the then-remote and dilapidated Long Island City in Queens – today, a hyper-gentrified neighbourhood with the highest density of artistic spaces in NYC. Noguchi found a warehouse whose vast open spaces were perfect for working on large-scale sculptures, big enough to install a living space too. In 1974, he purchased the triangular, red-brick corner building on the opposite side of the street to use as a future museum space. As the project expanded, Noguchi took over the adjacent gas station, razing it to the ground and replacing it with an entrance pavilion and indoor/outdoor gallery, transforming the courtyard into the sculpture garden that is today the complex’s flagship space. He transformed this derelict terrain vague, strewn with garbage and debris, into a landscape creation of the calibre of the Garden of Peace at the UNESCO Palace in Paris, or the Billy Rose Art Garden at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

Isamu Noguchi with The Roar in his Long Island City studio, 1970s. Photo: Stephen Chodoroff. The Noguchi Museum Archives, 04008. © The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / Artists Rights Society

In his transformation of desert into garden, employing a Zen approach combining artwork and environment, the whole operation vaguely resembles Derek Jarman’s garden assembly, not least in its meticulous selection of plant species and the incorporation of objets trouvés within the overall design (for the interior spaces, Noguchi retained exposed steel, wooden beams and metal ceilings to keep the building’s prior history alive…). But this is where the similarities end, because unlike Jarman’s largely manual and individual work, with its symbolic heroism because of his parallel battle against terminal AIDS, Noguchi’s garden assembly required the collective and mechanical work of bulldozers and diggers. Noguchi learned formal and ideological Zen gardening principles on one of his stays in Japan. Because Zen gardens are based on practically immutable, innovation-resistant principles, Noguchi hybridized them, transforming them into something else by adding contemporary influences, filling them in with concrete, putting in arched bridges that recall Carlo Scarpa, and in his final work – the Moerenuma park in Sapporo – going so far as to graft on structures with large mounds from archaeological civilizations. He was also impacted by European influences, from the beloved Greece that emerges in his sculptural forms to a breath of Mediterranean modernism in lines that recall Mirò, Calder, Picasso and Gaudi (his “Lunar landscape” sculpture is emblematic in this regard).

Isamu Noguchi, Akari light sculpture, 1972. The Noguchi Museum Archives, 03546. © The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / Artists Rights Society

For practical, display-related reasons, the stone works are concentrated outside, while interior rooms showcase the sculptor’s versatility in a variety of materials. In both cases, the sculptures’ settings make them unique works. Simple yet disturbing forms concretize Noguchi’s thesis that sculpture is “an idea in space conceived without obstacle”, that the destiny of art is to disappear, to become one with what is around it, ordered and meaningfully whole. Noguchi’s works are scattered all over the world, outside and inside the collections of famous museums and buildings, and yet with a natural extension in the most intimate, sculptural, locally-rooted garden in the village of Mure, on the island of Shikoku in Japan, closing the symmetry between West and East that is one of the lodestars of the artist’s research, he conceived the New York museum as an installation that, while being emblematic, comprehensive and complete, is also a summation of his work. Noguchi’s site-specific work has changed the horizon in this corner of Queens: the visitor’s gaze is no longer catapulted to the Manhattan skyline; it pauses among birch trees.

Stories

Stories