In partnership with MiCodmc, a selection of establishments ripe for discovery during the 63rd edition of the Salone del Mobile.Milano, from 8th to 13th April

A (summer) journey through the beach clubs that have made Italy’s history

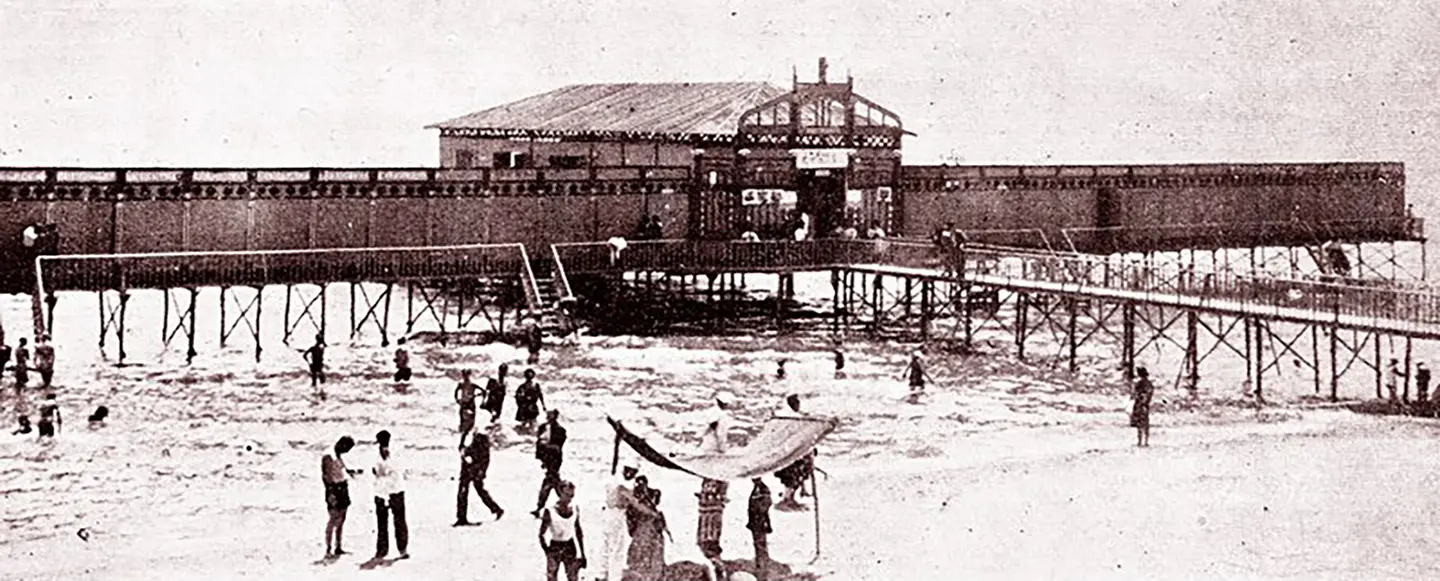

Postcard of the Rotonda a Mare, Senigallia, 1933

From Venice Lido to the Strait of Messina, passing through Viareggio and Ostia. A selection of the most iconic facilities that have dotted Italy’s coastline over the past two centuries.

The history of beach tourism is a key – although often overlooked – part of Italy’s architecture and customs. The mass summer exodus to the many beach clubs dotting the country’s coastline is a pretty recent phenomenon that started two centuries ago and that surged in the post-WWII era. It’s hard to say which is the oldest beach club in Italy, but we can say that Viareggio is the city that boasts the greatest number of them. The “prime suspects” are “Bagni Dori” and “Stabilimento de’ Bagni”, both dating back to the 1820s.

At that time, beach clubs used to be overwater wooden stilt facilities accessible from the beach via long piers. In the book “Manuale per i bagni di mare” by Giuseppe Giannelli, which was published in 1833, these resorts in Viareggio are described as “two comfortable and elegant wooden facilities, 65 arms apart, one for women and one for men. A wise and useful design: as, whilst those bathing are sheltered from the sun and from the glances of those strolling along the beach, water can reach them with the same motion as it would if they bathed in the open air”.

The resorts in Viareggio served as a role model for other accommodation facilities that were built later on in Rimini (1843) and on the Emilia-Romagna Riviera. Subsequently, they sprang up in Livorno, Venice Lido, along the Ligurian coast and in coastal towns like Naples and Palermo.

Bathing Establishment, Viareggio, 1827

The fascist era was a second golden age for beach tourism. They say that Mussolini himself was a great fan of the seaside. A resort that later became extremely popular thanks to the hit song Una Rotonda sul Mare, written by Italian singer Fred Bongusto (1935-2019) in the 1960s, dates back to this period. Rotonda a Mare in Senigallia is an emblem of tourism on the Adriatic coast and a symbol of the city’s identity. It opened its doors in 1933 and, since then, has been damaged and restored many times. Bongusto performed his famous song on the pier to celebrate its reopening in 2006. Today, it hosts exhibition spaces and a conference center.

However, it wasn’t until after the post-WWII era that beach tourism became a truly mass phenomenon. It followed the 1950s and 1960s economic boom, which brought about the so-called “Italian August”: a mass exodus of summer holidaymakers during the month-long shutdown of the largest factories in the country.

One of the most popular beach clubs in Italy at the time was undoubtedly Kursaal, which for decades has been a symbol of Ostia, Rome’s beach town. It was not by chance that Kursaal was the setting for movies that really made history, by some of the all-time greatest directors, such as Fellini and Dino Risi. It was built in 1950 thanks to the collaboration between architect Attilio Lapadula and famous engineer Pier Luigi Nervi. The complex is characterized by a number of distinctive structures, such as the restaurant, with its “mushroom” shape, and the trampoline, with its unique rounded iron ore cement structure.

Attilio Lapadula and Pier Luigi Nervi, Kursaal bathing establishment, Lido di Castelfusano, Rome 1950. Photo: Matteo Staltari

The Lidi di Mortelle complex, located on the Strait of Messina, also dates back to the 1950s, and was conceived as a true linear city that reinterpreted some of the most innovative international architectural trends of the time. Architect Isabella Fara from Palermo dedicated a book to this topic, titled L’architettura moderna va in vacanza. Una città balneare sullo stretto di Messina and published by Lettera Ventidue in 2011. Fara provides a detailed description of these beach clubs and of their “hybrid nature, by which they tend to borrow from different disciplines and naturally result from an assembly of buildings, systems or objects, which are part of a ‘collage city’ that is reassembled by the seaside”.

One of the most iconic and bizarre constructions from the 1960s is the chairlift in Lido di Spina, near Comacchio, in the Emilia-Romagna Region. This one-kilometer-long infrastructure used to run from Campeggio Spina, a campsite in the heart of a pine grove, directly to the beach. It was a comfortable way to reach the coast, even for those who didn’t own a car. With its 127 two-person seats, the chairlift used to take people to the beach in approximately 12 minutes. Apparently, however, it wasn’t a masterpiece of efficiency, since it was dismantled as early as 1974, officially due to problems associated with marine corrosion, but it was probably too expensive to maintain.

A more recent design (the last one in our selection) by Giancarlo De Carlo gave the celebrated architect an opportunity to reflect on the city and on its complex mechanisms. The Blue Moon beach club, which was completed in 2002 in Venice Lido, is a multi-purpose building designed and suitable for use all year round. Its core element is the round pavilion whose top floor is encased in a sleek grid-like steel structure. A spiral staircase stands in the middle of the space and revolves around a 34-meter-tall antenna: a landmark that is visible from all over the Lido.

Italy’s coast stretches for 8,300 kilometers. There are 27,335 beach concessions for “recreational tourism” purposes in the country. It is estimated that 60% of Italy’s sandy coastline is occupied by beach clubs. Moving beyond the nature/culture dichotomy, it appears evident that the architectural design of such places is a prominent feature that determines the country’s landscape. It is also evident that beach culture is a key part of our identity.

Stories

Stories